“The war has started” were the first words 15 year old Ann Tysevych heard when her mother woke her up on February 24, 2022. The thunderous bomb and sounds of warfare Tysevych thought were just a dream turned out to be reality. That Thursday morning marked the beginning of an indefinite change in life in Ukraine.

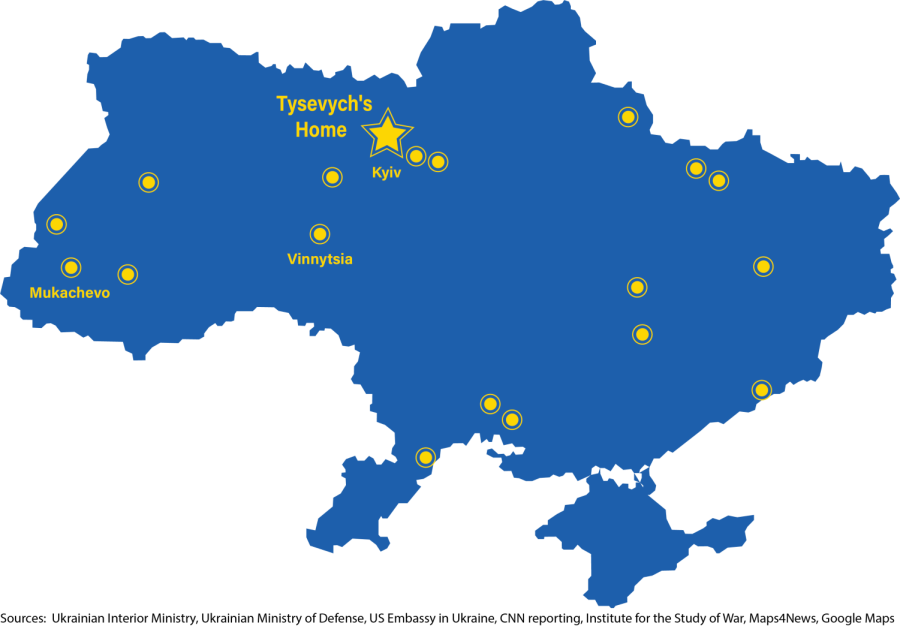

Living on the outskirts of Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, Tysevych was near several, early Russian attacks. She and her family were in shock when the attacks first began. Near Russia’s primary target, they knew it would be unsafe to remain in their apartment.

“We weren’t doing anything in the beginning [of the attacks],” Tysevych said. “I started telling my parents that we should definitely do something, that we needed to go somewhere before it got even worse.”

According to Tysevych, leaving home was chaotic, almost apocalyptic. She and her parents drove in the car-packed streets, bumper to bumper, for over three hours to her grandparents’ house in Vinnytsia. The next day, they drove further west to stay with her other grandparents in Mukachevo.

“We stayed at my grandparents’ for 3 months,” Tysevych said. “For the first two months, my whole family was there, but then my parents decided to start volunteering or do some work in Kyiv.”

Her parents returned to Vinnytsia to volunteer with food and supplies. After staying for a few weeks, her parents returned to their jobs in Kyiv to support their family.

Tysevych joined her parents in Kyiv at the beginning of the summer, around four months after the beginning of the attack, they felt uncertain of what the future would hold.

“I wanted to believe that [the war] would not last for a long time,” Tysevych said. “But when we saw news that Russian soldiers were almost in Kyiv, it’s hard to believe it is not going to last long when they are close.”

Now almost one year since the start, the constant attacks and constant fear of her family’s safety is Tysevych’s new normal.

Her life before war was like any other teenager’s. According to Tysevych, she would go to Kyiv to hang out with friends, eat out, and spend some time by the Dnieper river that separates both sides of the city. Tysevych attended school in person and went on vacations with all of her family.

For Tysevych, the first two months of the war were the hardest and most depressing. She was not attending school and had nothing to do at her grandparents’ home.

According to AP News, in September 2022, 51% of Ukrainian schools opened for in-person education, with the option of remote still available. With safety concerns still in mind, schools that do not have quick access to shelter or are located close to active war zones still remain online.

“Some schools have big shelters that let the whole school be hidden inside the shelter,” Tysevych said. “My school doesn’t. Only first through fourth graders are going to my school.”

As a sophomore, Tysevych continues taking lessons virtually, due to the capacity limit that her school’s shelter holds.

According to NPR, since the Russian invasion in February up until September 2022, 2,177 education facilities have been damaged and 284 have been completely destroyed.

Online school has not been easy, according to Tysevych. Along with the struggles of virtual learning, Tysevych has to deal with power and wifi shortages.

“Russia destroys our electricity factories,” Tysevych said. “We then have no light or heat in our house. It would be nice to have light all the time.”

Most Ukrainian cities’ send electricity to valuable locations, like hospitals. To deal with this problem Tysevych’s family bought a generator.

“Now we have better generator so we have better wifi,” Tysevych said. “It was a problem for me because I had no light and no connection so I just didn’t go to lessons.”

Due to the attacks and restrictions, hanging out with friends has become dangerous and confined.

“When there is an alarm my parents won’t allow me to go to Kyiv because it is really dangerous,” Tysevych said. “Rockets are usually sent to the center of Kyiv… I cannot remember the last time I visited.”

The alarms limit many activities, as restaurants and malls close whenever an alarm sounds. According to Tysevych, she is still able to enjoy time out, which she feels is lucky in comparison to many cities in Ukraine.

“I have my family, my house, my friends, and we still hangout,” Tysevych said. “Cities like Kherson were occupied within three months and people were not able to get out, markets were changed by soldiers.”

According to Le Monde, the number of Russian controlled territory has decreased as the war continues. In March 2022 Russia controlled 25% of Ukraine’s territory and in November, Ukraine was able to lower the number to 15%.

“(The Russians) are not only destroying our military items, they are destroying innocent’s houses, kindergartens…” Tysevych said.

As of January 22, 2023, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights verified 7,068 civilian deaths as of Russia’s Invasion 438 of those deaths were children and 11,415 people have been reported to be injured, according to Stastica. However, it is predicted that the number of injured could be higher.

Even though Tysevych’s life has taken a complete turn, she remains in Ukraine due to her mother’s wishes. According to Tysevych, her mother was extremely stubborn in wanting to stay in her home country and no matter the danger, she wanted to help.

“It is hard to do something in a situation like that,” Tysevych. “My parents would never leave Ukraine… if only you could see how my mom was crying, she felt like she couldn’t leave and had to help.”

Many Ukrainians feel this same prideful attachment to their home country. Many citizens have taken it upon themselves to stay behind and help.

“I really realized that Ukrainians are really brave people and we will really do anything for our country,” Tysevych said. “Our people are not giving up.”

As the war goes on many Ukrainians have felt the need to isolate themselves culturally from Russia. Many Russian items and traditions are being changed and not practiced in Ukraine anymore.

“Before war a lot of people listened to Russian music and there was no problem,” Tysevych said. “It is really important to stop listening to their music to stop giving Russia money. They are using the money and turning it into bombs and rockets.”

The war has been an unexpected experience but Tysevych feels that the help from the rest of the world has been really valuable.

“I am grateful that people are helping Ukraine,” Tysevych said. “It is really helpful to just share information, repost something to your Instagram…this helps more people see and know what is happening.”