It seems like every year there’s a new diet trend that has gained popularity or a food that has been deemed “bad.” The Atkins diet, the cabbage soup diet, the grapefruit diet, the raw food diet, juice cleanses, meal replacement shakes, Whole 30 — there are just so many. And most of them are no longer prevalent and have been proven ineffective for healthy and sustainable weight loss. So why were they even popular in the first place if they lacked scientific evidence? Simple — diet culture. It promises people a quick way to become skinny, which is then equated with happiness. Diet culture is driven by the same force as any marketing campaign, and the way to defeat it is by raising awareness and recognizing how ingrained it is in society.

First, there’s a difference between promoting diet culture and promoting a balanced lifestyle. The Harvard Chan School of Public Health firmly states that “research has shown that individuals following five key habits—eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, keeping a healthy body weight, not drinking too much alcohol, and not smoking—live more than a decade longer than those who don’t.” Diet culture doesn’t take this same holistic approach. Instead it offers one fix — sometimes an unsafe one — towards being skinny, which is not the same as healthy. It disregards each body’s unique needs and creates a trend of body dysmorphia.

Worth about $72 billion according to The Associated Press, the diet and weight loss industry reinforces people’s insecurities that they are overweight to then persuade them to use some product or try some diet that will supposedly make them skinnier. It is a larger part of American society than many realize and manifests itself in various ways, whether it be through media, film and television or just everyday life. The National Eating Disorders Association claims that by 6-years-old, young girls are already distressed by their body size, and 40-60% of girls between the ages of 6 and 12 “ are concerned about their weight or about becoming too fat.”

Physical education teacher Amanda Dean recognizes this trend and teaches nutrition in health and wellness class from a standpoint that emphasizes each body’s unique needs and responses to food.

“There’s so many different diet plans out there, and if you asked 100 different nutritionists what the perfect diet was, you’d probably get 100 different answers,” Dean said. “So I don’t try to tell them how to eat. I want them to understand what the nutrients are and what different types of food are giving them as far as nutrients go, and then you can make those decisions for what and how you want to eat on your own.”

The mentality of diet culture, that skinny equals healthy, healthy equals better, and therefore skinny equals better, is further perpetuated by social media, where people, especially celebrities, can use filters and photoshop to alter their appearance. For example, the Kardashian-Jenner family is known for accepting sponsorships for and promoting different weight loss remedies. In 2019, Khloé Kardashian was criticized for advertising products from the company Flat Tummy Co, which included meal replacement shakes, detox teas (laxatives) and appetite suppressants. The diet industry was able to reach her over 100 million Instagram followers, many of whom are young people, to convince them that in order to look like a megastar, who in reality has a personal trainer, styling team and editing software, they need to basically starve themselves of the nutrients their bodies’ need.

“What they’re doing is feeding off of you feeling like you don’t meet up to societal standards, and that’s horrible,” student Meredith Swift said, who asked that her name be changed for privacy reasons. “All you should be focusing on is am I getting enough nutrients and am I getting stronger. Or am I moving? Am I taking care of my body? Am I making myself better, mentally, and making it better doesn’t mean skinnier at all. In fact, in some cases, it means getting bigger.”

Swift has struggled with an eating disorder since November 2019 and said that it was mostly caused by social media.

“I think social media was a giant part of it,” Swift said. “I constantly felt like I wasn’t skinny enough … It started as I thought I was being healthier because I went through Instagram, actually, is where it all spiraled because I was looking for healthy recipes, and so I would find healthy recipes. The only problem was their version of healthy was low-calorie, and I bought into it, I totally bought into it. I was convinced that rice wasn’t okay. Instead you have to eat cauliflower rice because it’s 10 times less calories.”

Swift said it got so bad that she could outline the bones in her hands and feel her bones on the chair when she sat down. Swift was never medically overweight but admits that she gave into societal standards, as even before her eating disorder, she was still dissatisfied with her body image.

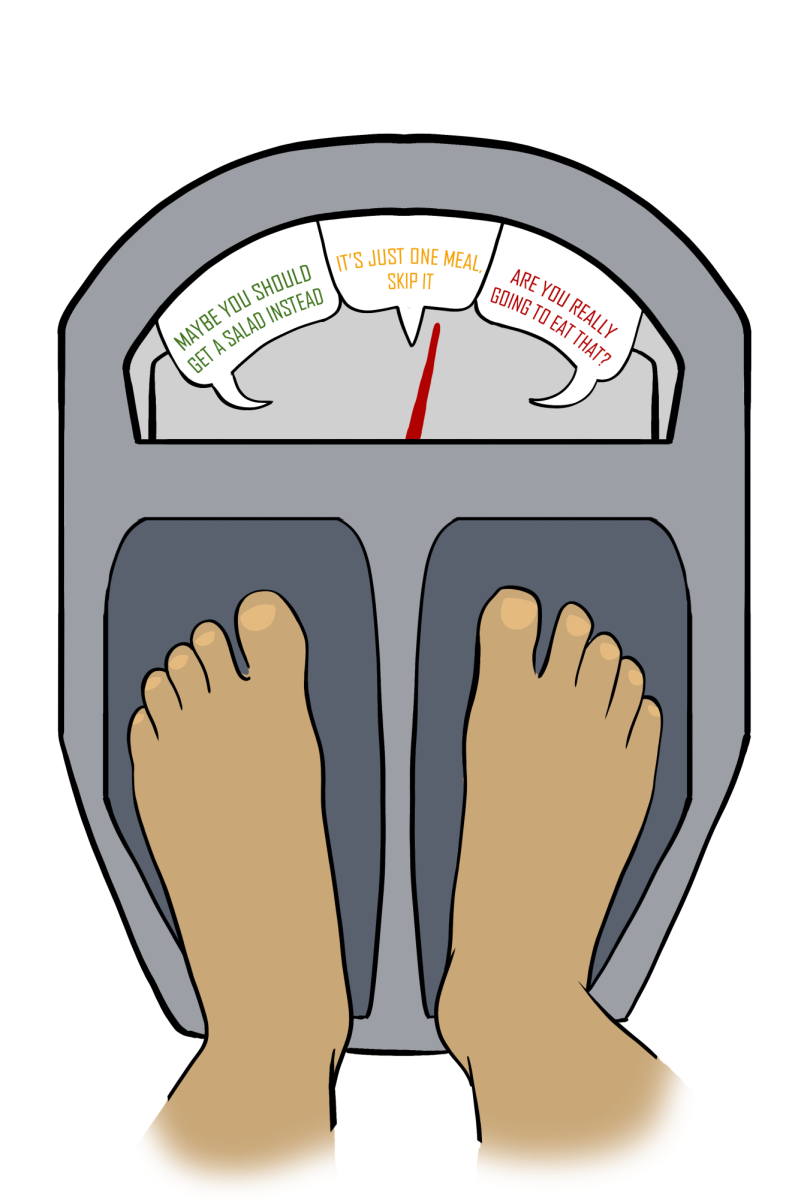

A study performed by the National Center for Health Statistics under the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that many Americans can relate to Swift’s mentality. Between 2013 and 2016, the study found that 26.5% of underweight or normal weight Americans ages 20 and older attempted to lose weight, 14.4% of men and 35.6% of women. Of the adults in all weight categories, 16.4% said they skipped meals in order to reduce weight, which is not safe and actually has the reverse effect of weight gain, according to the University of Louisville.

In 2003, the American Journal of Public Health analyzed “five episodes of each of the 10 top-rated prime-time fictional programs on 6 broadcast networks during the 1999–2000 season.” It estimated that 31% of the series’ female main characters and 12% of the male main characters were underweight, compared to 5% and 2% of the American population respectively. Overweight people on the other hand were underrepresented, with only 13% of the female characters being categorized as overweight or obese, compared to 51% of the female American public.

That same study further asserted that larger characters were less likely to provide helpful assistance when characters were doing tasks, less likely to have a romantic exchange with another character and less likely to be thought of as attractive than their “normal” and underweight counterparts.

Subsequently, people subconsciously internalize what they see in the media, according to an article published in the National Library of Medicine. The article outlines a study conducted in three Nicaraguan villages — one urban one, one rural with access to television and one rural with some access to television. The urban village where people had the greatest ability to watch television preferred women with the lowest body mass index (BMI), and vice versa. The people from the remote village with some access to television had the highest BMI preference; the village with the in-between access to media fell in the middle of the other two.

Similarly, guidance counselor Rylan Smith has seen an increase in body image issues coincide with the development of social media.

“We’re so absorbed with how we look that I think it’s [being concerned with how oneself looks] a little bit more [present] than it used to be,” Smith said. “I think some of it’s very normal because growing up we all want to be our best, look our best, do our best, but I think having the technology of the cell phone and having the social media to compare ourselves to has definitely made this a bigger concern.”

She believes that one way to combat this problem is to appreciate the differences and strengths that are unique to each individual.

“I think the biggest thing we can do is to continue to have dialogue that normalizes the concept that you are enough in your own skin and that you don’t have to compare yourself to other people and that everybody’s different,” Swift said. “By normalizing that conversation, it’s going to have to happen over and over and over and people are really going to have to buy into that, and that’s hard.”

Against all the still ever-present diet culture, it seems like there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Dean has noticed an increase in representation of plus-sized models and actors.

“I think that there’s been probably in the last five years a bigger push, in the general media, about loving the body that you’re in and [there’s been a] backlash against the body shaming,” Dean said.

Swift recognizes the importance not of body positivity, but body neutrality.

“Yes, body positivity, but that still puts emphasis on what you look like,” Swift said. “‘That still says ‘even though you have fat, you’re still okay.’ Like no, we all have fat, and all bodies are kind of irrelevant. We should be judging each other based on our actions, our words, not the bit of fat we have on our thighs or the bit of fat we have around our waists. What does that tell you about the person? Nothing! Literally nothing. It doesn’t measure worth; it doesn’t tell you how well you’re going to succeed at your job or life or whatever; it doesn’t tell you how happy someone is. It’s just a little bit of fat.’”