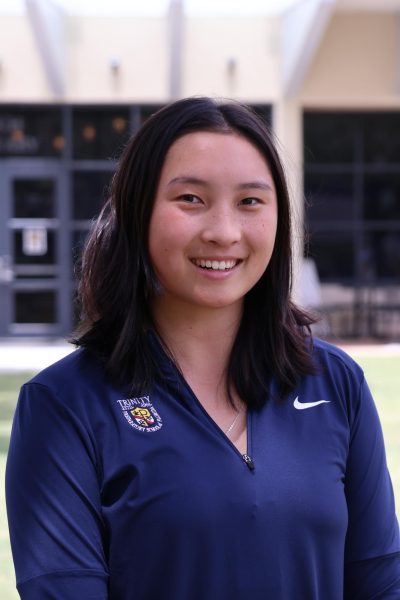

Freshman Simar Kang finds his usual spot in the darkness of the surrounding park and sets up his Barlow lens, telescope and camera. Although he can not see much around him, the darkness is his friend, illuminating the faraway dance of stars and planets in the night sky.

Photo by Simar Kang, used with permission.

“[When] I looked through it, I saw craters on the moon, the rings of Saturn and Jupiter’s moons,” Kang said. “And I [was] like ‘Wow.’”

Recording pictures of the night sky is a frequent occurrence for Kang. But even before discovering astrophotography, he was fascinated by space.

“My first interactions with space pretty much began when I was around 6, and I saw a lunar eclipse,” Kang said. “It was super cold out that night, and I looked and saw the moon turning. I thought that was really cool.”

Interested in anything involving space, Kang stumbled upon a YouTube video by astrophotography channel “AstroBiscuit.” The video opened a new world for Kang as he began exploring the ins and outs of capturing these celestial objects — first with the purchase of his own professional Dobsonian telescope.

“I pretty much discovered it on my own,” Kang said. “I looked at their videos since they have quite a few tutorials. I took inspiration from those projects and also looked things up.”

Since then, Kang has completed several projects over the span of these three years and established his own techniques. Along with the Dobsonian telescope, he uses a dedicated astronomy camera (ZWO ASI 585 MC Pro), which attaches to the telescope. On top of his main equipment, a field flatter, which ensures no stars are stretched or blurry, and a de-rotation device are necessary to accommodate for the rotating nature of Earth. With plenty of practice, dealing with these complex devices became routine.

“I’ve mastered processing techniques and such to really get what I want and keep all those [unnecessary] artifacts out,” Kang said. “In general, set-up time has gotten a lot lower since I first started because you have muscle memory. As to what goes where, how to do everything, you pretty much have that all set in your brain.”

Each project begins with Kang looking for targets on the astronomy app Stellarium. Usually, he has a period of two to three months in which he can best capture the target.

After scheduling the day, he heads out around 9 p.m. and images for around two to three hours; during which, the camera captures around 500 frames. From there, he transfers the information onto his computer, using a stacking software to combine them into one cohesive image.

While some photos come out well, others may feature an unexpected appearance of a white trail seemingly made by random satellites, rocket boosters or meteors captured in the moment.

“You can see all that data,” Kang said. “I’m either like ‘Really? Is that really all I got?’ or ‘Wow, that looks great.’ I was amazed that I got that data, especially from a light polluted sky.”

Sometimes in order to capture all the sufficient data, the capturing process may take days. In Kang’s upcoming project, he plans to capture the Crab Nebula — a supernova remnant of a star that exploded in the 10th century — which will take over three nights in a total of nine hours to capture. Along with the skill of shooting these frames, Kang found that the entire process of astrophotography also helped him embrace subjects that he never found much interest in — including math.

“I’m not someone that likes math, but some of this stuff requires an ethos, FOB calculating and seeing if your pixels are going to line up with the telescope,” Kang said. “ ere’s a bunch of formulas you have to do, and yeah, I stopped hating math.”

But no matter how complicated the process is, Kang finds astrophotography as a labor of love in which he unearths the remarkable place that is space.

“Just simply looking at people’s pictures, seeing how beautiful space is, what sorts of objects are just in the sky waiting to be seen and overall seeing those objects like the planet craters on the moon cemented the whole thing in my brain,” Kang said.