Every high school student dreads the difficulties that come with standardized testing. However, a budding alternative is making its way into the mainstream: the Classic Learning Test. (CLT) Created by Classic Learning Initiatives, a for-profit company, the CLT has a strong focus on traditional education that has been met with widespread disapproval and backlash from politicians, educators and College Board due to its conservative backing and lack of supporting evidence of its efficacy.

In September, Florida became the first state higher education system to approve use of the exam in the college admissions process. The decision was made by the governing body for Florida’s public university system (Florida Board of Governors), composed mostly of members appointed by Governor Ron DeSantis. In May, DeSantis also passed a bill that approved the CLT’s use as an accepted test for the Bright Futures Scholarship Program. While these policies serve to disrupt the duopoly held by the SAT and ACT in the standardized testing space regarding admissions, English teacher and standardized testing tutor Dr. Robert Boerth believes that they are unlikely to make a significant difference.

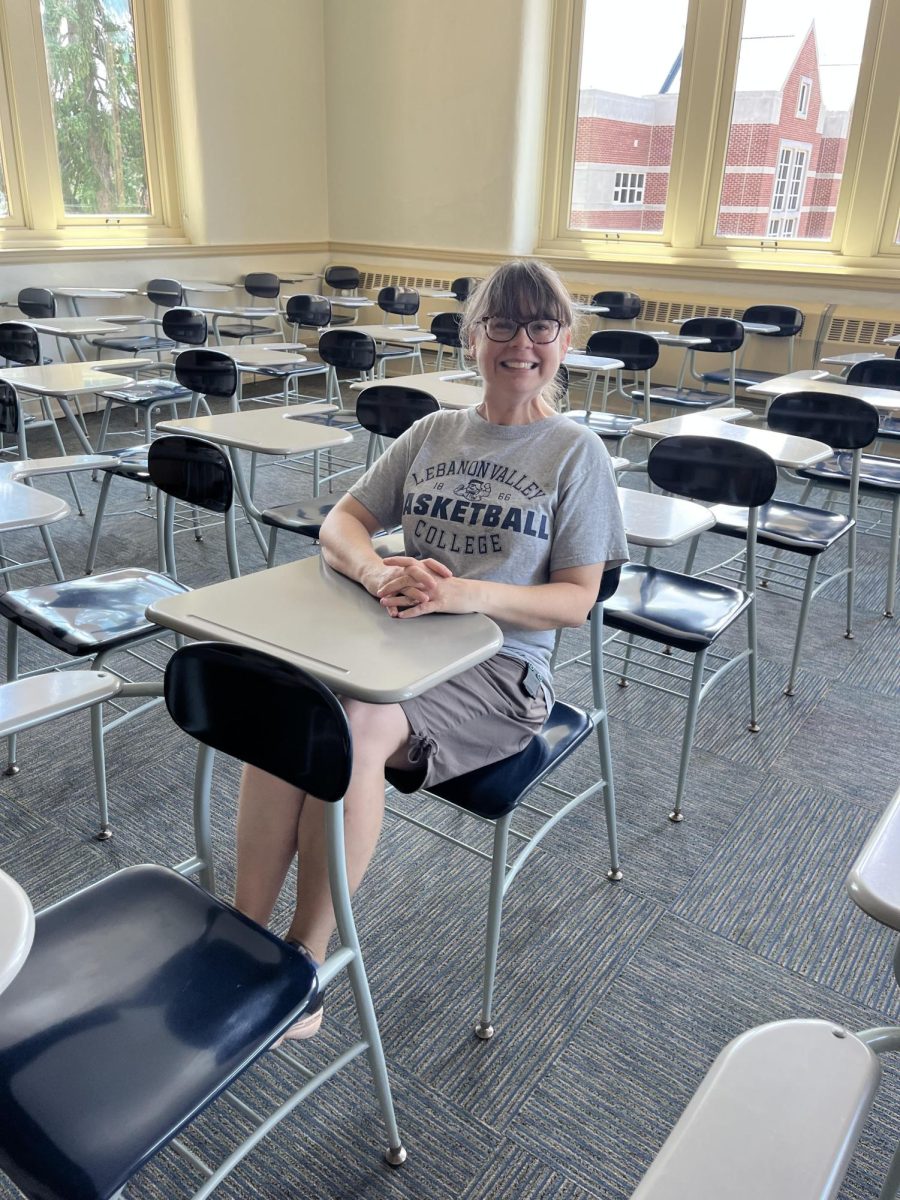

“Given the track record and the number of students that are currently taking the SAT and the ACT, I think it’d be very challenging for a test to come along and significantly challenge the foothold that [these tests] have already established,” Boerth said.

Prior to the CLT’s approval under DeSantis’s bill, the test had been widely struck down by the majority of major public and private institutions and was only adopted by a select niche consisting of small, private Christian colleges and liberal arts universities.

“There was definitely political pressure for Florida public schools to accept [the CLT],” college counselor Christine Grover said. “Currently in Florida, they are trying to talk the private institutions into taking it, and they are meeting resistance.”

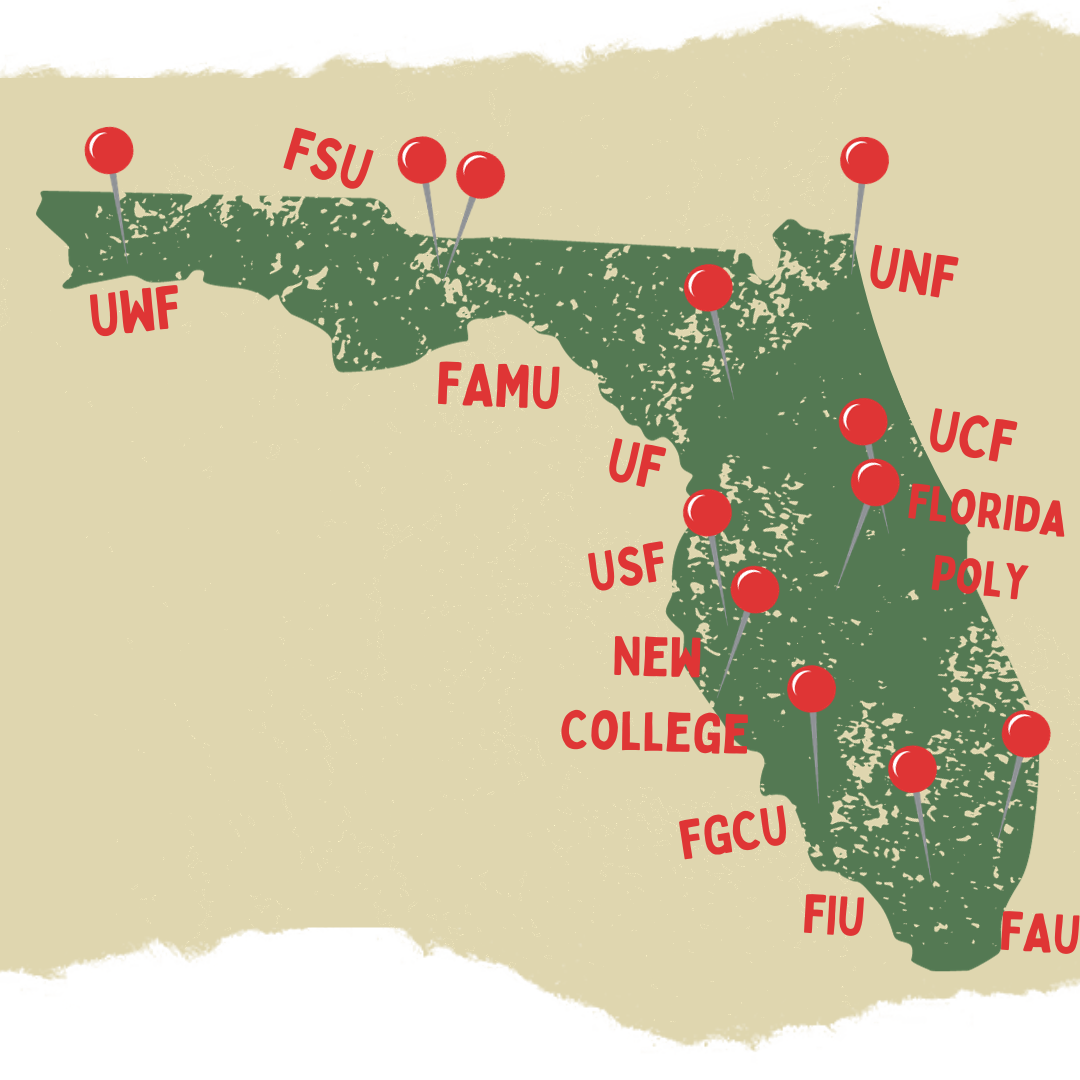

Twelve public universities including the University of Florida, the University of Central Florida, Florida State University and the University of South Florida are obligated to accept the CLT when considering applications, widening its potential application pool by hundreds of thousands of Florida students.

This sudden addition of Florida public universities to a system that was previously made up of only 15 private institutions proves beneficial for in-state applicants–specifically those in search of Bright Futures scholarships.

The state-funded Bright Futures Scholarship Program offers in-state applicants the benefit of free tuition at any public Florida university while also providing financial incentives for private institutions by meeting certain standardized testing thresholds, along with a 3.5 GPA and 100 hours of community service. Following Governor DeSantis’s May legislation, the CLT has become a viable option to qualify for this highly regarded scholarship.

“For students who haven’t been able to hit 1340 [on the SAT] or 29 on the ACT, I would recommend they try [the CLT],” Grover said.

While the CLT’s state-wide approval is a forward step for its legitimacy, the test has come under much scrutiny in recent months. Amanda Phalin, Florida Board of Governors member and sole objector of the 13:1 vote regarding the CLT’s approval for college admissions, opposes its use because “[Classic Learning Initiatives] does not have the empirical evidence to show that this assessment is in the same quality as the ACT and the SAT.”

The CLT’s reach has been notably limited when compared to the SAT and ACT. According to College Board, from 2016 to 2023, a mere 21,000 high schoolers across the nation took the CLT. On the other hand, in 2022 alone, 1.7 million and 1.3 million took the SAT and ACT, respectively.

This significant variation in sample sizes raises questions about the CLT’s compatibility with other standardized tests. In a brief published by College Board, the CLT’s concordance study was criticized for its small sample size and lack of test rigor; the brief concluded that 25% of questions administered by the CLT were below a high school proficiency level. These factors render it challenging to standardize scores when compared to widely recognized tests such as the SAT and ACT.

Unlike the SAT and ACT, the CLT’s lack of standardization threatens the solidity of the scoring threshold students have to reach in order to qualify for the Bright Futures Scholarship Program. As a result, according to Grover, Trinity is hesitant to use the CLT for admission this year with its current applying seniors.

“Any nationally standardized test needs to be able to establish that it is legitimate in terms of the way that it’s assessing students,” Boerth said. “And that’s what the CLT lacks.”

The CLT’s controversy is not only limited to its legitimacy, however. The test is closely tied to Florida’s right-wing politicians and is being propelled into the limelight as yet another chapter in Governor DeSantis’ conservative education reform.

While this political association may limit the CLT’s national expansion as it attempts to compete with the SAT and ACT, some predict it could persist in Florida by capitalizing on the state’s educational policy changes.

“I think [the end goal of the CLT] depends on the political climate of Florida,” Grover said. “It’s been around for years in very conservative and religious institutions, and although it is possible that other conservative states might adopt this for their state institutions as well. I don’t think it will spread beyond that.”