In 2003, a Harvard sophomore used his proficient coding skills to create a new site called Facemash. The concept was simple; it took two pictures of girls’ student IDs and allowed the user to choose the prettier one. That choice would then be put into an algorithm to produce a ranking of all the girls at the university. This was attractive to Harvard students, accumulating around 22,000 votes in two days. While FaceMash was short-lived, the creator’s 2004 invention, Facebook, would take off, gaining billions of curious users and forever changing the way people connect on the internet.

While viewing successful people on social media can be seen as motivating, it can also give viewers a false perception of identity. Social media is marketed as a way to connect people, but it isn’t what it is made out to be. Many users, famous or not, manufacture perfection; they create a life of what people want even if it barely resembles their own.

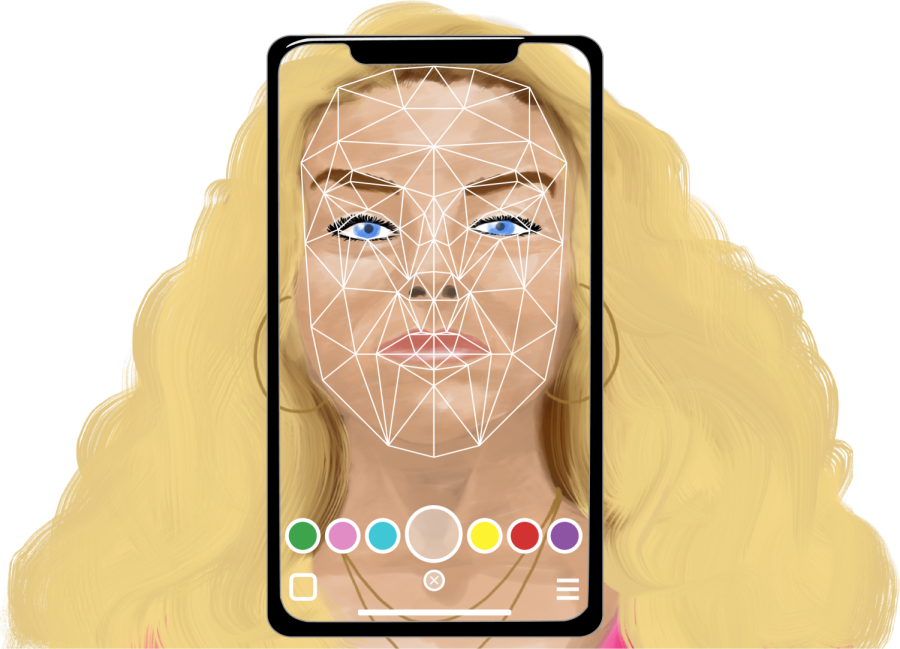

It would be naive to think that beauty standards are a new thing. From organ-crunching corsets to mercury-filled cosmetics, there is no measure too extreme if it means achieving a perfect look. However, before the rise of social media, it took a lot more than a click for people to see a deceptive model of perfection.

“I know growing up, compared to now, it feels like I was only looking at people either that I saw day-to-day or in magazines,” guidance counselor and administrator Rylan Smith said. “Now I think you all have such immediate access to people from all over the world. People that are photoshopped, or with certain lenses on, [give] this false image of what perfect is, and everybody feels like they have to fit that model.”

Overexposure to beauty standards and the rise of new insecurities is a direct response to the rise of social media. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey of 750, 13 to 17-year-olds, found that 45% were online almost constantly and 97% used a social media platform such as Youtube or Facebook. However, social media is so intertwined with a person’s daily life, it can be hard to identify it as the root of the problem.

Despite it not being a recognizable cause, social media companies have attempted to try to hinder this toxic side of their platforms. For example, Instagram has attempted to help the problem by giving users the option to hide the number of likes a post gets.

However, simply hiding the number of likes on a screen is an almost nonexistent step to solving the problem. They hide a number on the screen then sweep under the rug the photoshop, lies, self-doubt and overexposure their app provides. Instagram wants to appear like they care about the burden their site puts on users, but in reality, they don’t. Even when they seem like they are trying to promote inclusivity and acceptance, it is just a small band-aid on the cut of insecurity they have put on their users.

Part of the addictiveness of social media is how a user can build their own world in it. They can post what they want people to see, and they can view people they want to become. Social media companies know the power these ideals have on their users.

They use them to keep people addicted. The user is lost in a mental trap that proposes an escape from stress, but they are actually being pulled in deeper.

“I would love for the social media platforms to tackle [beauty standards], but I don’t think they’re going to because ultimately, they’re a business,” Smith said. “And while they do believe they care about their users, they have to look at it from a business perspective, not from the user perspective.”

It is not only the companies that reap the benefits of these beauty standards but the “perfect” users themselves. For example, the Kardashian family rose to fame through reality TV and have been dominating the public eye for the past decade.

The Kardashian sisters have become a caricature of a perfect-looking woman. The problem is their beauty, even when it is natural, cannot be attained by most people.

Their lifestyles and careers allow them access to the best personal trainers, nutritionists, dermatologists, photoshop editors and, when all else fails, plastic surgeons. When they attain this artificial beauty, they then use Instagram as a vehicle to share it. They repeat endlessly that their looks are achievable with just some hard work. It isn’t a day in the doctor’s office that allows their lips to grow, but instead, it’s their new lip kit that you can buy right now. These people need to preach the possibility of perfection, so eventually, their jealous viewers will purchase their goods to aspire to something that is not even real.

Users are lured into social media through the false promise of connecting with friends, but they are trapped by their desire to achieve what the “perfect” users achieve. Social media companies have no incentive to prevent this trap, so to hinder a rise in insecurities and malicious facades, it is important to spread awareness about the effects of social media. Something as simple as unfollowing a toxic page on Instagram or taking a break from a certain application can lessen social media’s negative effects.

“What I try to stress to you all, and even to adults that struggle with this, is to remember that it is just a blip in somebody’s day; it’s not who they are,” Smith said. “Even if they post 50,000 times a day, it is just looks. It’s not really who they are as an individual or who you are as an individual. It’s just what you are choosing to share, and so we have got to keep all that in perspective.”

As social media and social media companies grow in power, the users must start prioritizing their mental health first. It is important to stop letting some man in Silicon Valley, whose first taste of success was creating a website to rank girls, dictate what “perfect” is.