Indentured servitude in the NCAA

By: Daniel Stein

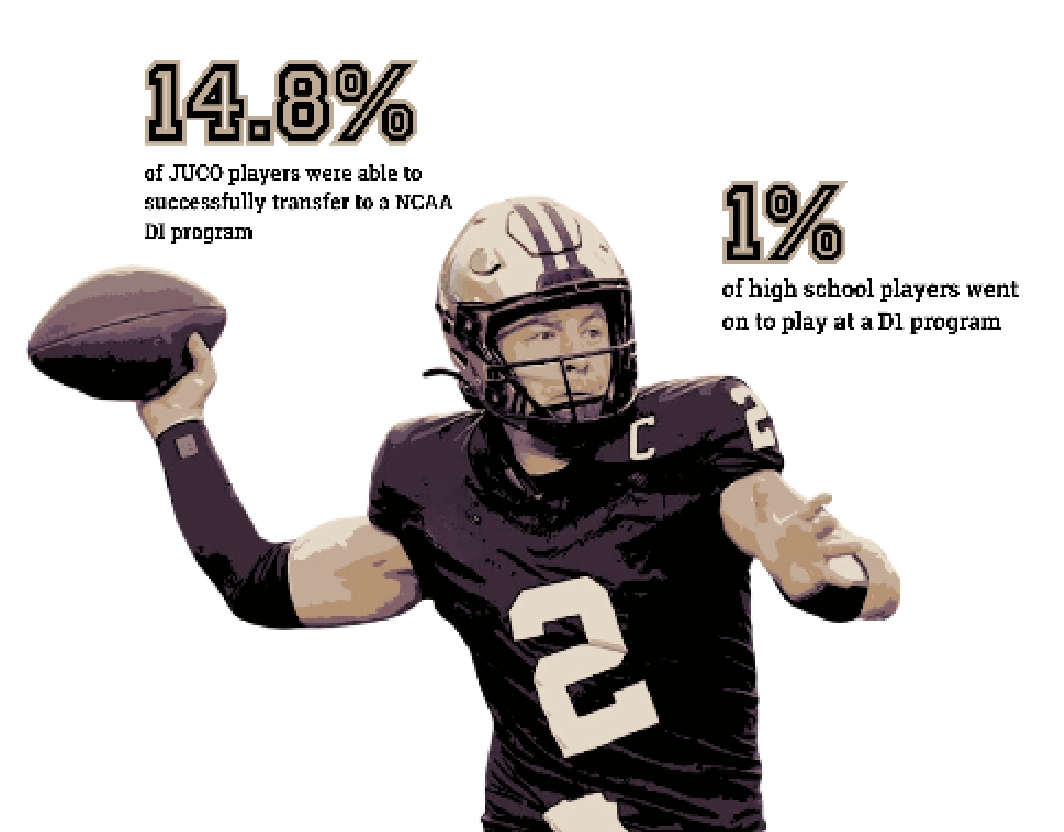

Collegiate athletics are one of America’s passions. Whether it be football or basketball, Americans love college sports. The National Collegiate Athletics Association, or NCAA, is the sole corporation that runs all American collegiate sports. They have established a complex set of rules preventing student athletes from making money or receiving cash gifts while they participate. Johnny Manziel and Kevin Sumlin both work 15 weeks a year for Texas A&M. Sumlin, the head coach, gets paid a comfortable $3.1 million dollars a year. This is $3.1 million more what Johnny Manziel makes. Although he brings in $37 million dollars of revenue a year, Manziel is not paid a dime.

The NCAA is a multi-billion dollar corporate entity. Despite this, they refuse to pay their “employees”—excuse me—the athletes who participate. The student athletes must attend class, do homework, and take exams and tests. Yet they still find time to practice their sport, stay in shape and play in games week after week. The student-athletes earn millions of dollars for their schools in merchandise, ticket sales and lucrative television contracts.

Some collegiate athletes are fighting back. According to ESPN writer Adam Schefter, Heisman trophy winner Johnny Manziel is suing a vendor at Texas A&M for selling a jersey with his name and number on the back. To Manziel’s dismay, the NCAA allowed the vendor to keep any money that he made selling that jersey. Texas A&M now sells Manziel’s jersey, without his name, and the quarterback can do nothing to stop them. ESPN’s Rick Reilley adds that Manziel is worth $37 million in free advertising to his school. Thanks to the NCAA, Manziel will not see a penny of that money. He is a torn ACL away from being a poor sophomore sitting in Chemistry 101.

Recently, Houston Texans running back Arian Foster admitted to accepting money while attending the University of Tennessee. Foster explained in an interview with Sports Center that he had almost no money for food.

“Our stadium had like 107,000 seats—107,000 people buying a ticket to come watch us play. It’s tough just like knowing that, being aware of that,” Foster said.

He described a time when he returned to his dorm after practice and realized his fridge was empty. “Our coach came down [to our dorm] and brought 50 tacos for four or five of us, which is an NCAA violation,” he said. Foster is a firm believer that athletes, who he sees as employees, should be paid for their work.

The SEC brings in $3 billion from its television deal with ESPN and CBS. In 2010, the NCAA agreed to a $10.8 billion contract and the Big Ten has its own television network, which generates $242 million in 2011.

Athletes are the reason that viewers tune into these networks. Though it may be entertaining, sports fans do not watch the NCAA Championship Game for the halftime show.

The National Championship game in men’s basketball is a great example of why the athletes should be paid. In 2013, Louisville took on Michigan in the most anticipated game in all of college basketball. It featured some of this year’s best players—Russ Smith, Trey Burke and Tim Hardaway Jr.—all of whom are underclassmen. Just as college basketball fans were ready to start following these players for next year, they bolted for the NBA draft. This is because the players want nothing more than to make money playing the game that they love. No matter what they say about “wanting to win a championship” the big thing on their mind is that multi-million dollar paycheck they will sign after the draft. They cannot afford to stay in school when the prospects are good elsewhere

The NCAA system is designed to live under the concepts of amateurism. Some college sports may still have a good degree of amateurism, but it’s hard to argue that players like Trey Burke resemble anything of that. His name would trend worldwide during games and, like Manziel with Texas A&M, he has made the University of Michigan millions of dollars. The only reason he was considered a non-professional was because he didn’t actually receive a salary.

The biggest question that is brought up during this argument is should all collegiate athletes, regardless of their sport, be paid? According to Michael Wilbon of ESPN, Nick Saban, the head football coach for Alabama, makes $5.9 million dollars a year. The highest paid professor at Alabama makes a small fraction of that. Not everything is equal. Capitalism exists in America and sports are no exception. So, the answer to the question of all athletes being paid would be no. Only the sports that produce a major part of the school’s revenue should be paid. Typically, that includes football and basketball. Baseball, soccer, track and lacrosse, though all popular college sports, will likely be excluded as they bring in little revenue.

There is a simple solution to all the problems discussed. Upon recruitment, Division I athletes sign a four-year contract which pays them a small base yearly salary. For those four years, athletes are just that, athletes. They are not officially enrolled in their university and do not attend class. They play their chosen sport, and they are guaranteed admission to the college upon completion of the contract. After their four years as an athlete are over, collegiate players would have the option of turning fully pro, taking advantage of their guaranteed admission to their college or taking their fair-market compensation out into the world as an adult.

The world of college sports is complicated. Because the intrusive NCAA has taken over the lives of college athletes, players are more inclined to only stay the minimum amount of years before turning pro. Even if the colleges shared merchandise revenue with the players, everyone would benefit because more merchandise would be sold if players remain in college longer. Unlike baseball, which has a professional minor league system as an alternative to college, football and basketball players must go to college before heading to the professional ranks.

If the athletes are compensated financially while in college, they will be more inclined to stay four years and earn their degrees. It is time for colleges to pay their fair share.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Pay for play? Not in the NCAA.

By: Natasha Haralambous

Putting Johnny “Football” Manziel of Texas A&M on the cover of its September 16 issue, Time magazine asks this question: “Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel is worth millions to his school, his town and college football. Where’s his cut?”

Manziel won the Heisman Trophy in 2012, which is awarded annually to the person deemed the most outstanding player in collegiate football. After an autograph broker told ESPN that Manziel was paid $7,500 for signing approximately 300 mini- and full-sized helmets while attending a non-proft summer camp, the simmering debate about whether college athletes should be paid returned to the front of national discussion.

Some argue that college athletes, such as Manziel, should be paid because their colleges and the NCAA have exploited them, profiting handsomely off their athletic prowess. However, college athletes are already compensated through scholarships.

“College athletes are receiving a free college education, room, board, books and free tutoring services,” Athletic Director Kathy Finnucan said. “In essence, they are being paid to attend that school.”

At bigger, more successful universities, athletes also receive free academic counseling, life skills training and even nutritional advice. It may make sense to compensate those college athletes who don’t receive full scholarships or any scholarships at all, but those players are generally in non-revenue generating sports such as soccer, swimming and tennis. If colleges compensate athletes of non-revenue sports, they would actually be losing money.

“As far as paying college athletes, where would the money come from or would schools raise the tuition to cover this?” Finnucan asked. “If they are going to start paying their athletes, the schools would have to increase their tuition.”

If tuition increases, fewer students would want to attend the school, leading to a possible decrease in total revenue for the school. Ultimately, adding direct pay to college athletes would put financial pressure on schools to drop non-revenue sports.

College Connections

Having had the opportunity to make lasting contacts with donors and boosters while representing the school, a student-athlete has a significant advantage in receiving a high-profile job right out of college. An athlete like Manziel, whose declaration for the NFL draft is no doubt on the horizon, will have big-time Texas A&M boosters paying big money for his services once his NCAA eligibility runs out.

“During college, high profile athletes make many connections that will greatly benefit them in the future,” Assistant Athletic Director Drew Nemec said. “By gaining fame and notoriety in college, it will be easier for them to enter the workforce. Also, if a college athlete is smart, they’ll do everything possible to get internships at companies owned by boosters to their university that will give them experience in case those professional dreams don’t come true.”

Alum Meg Casscells-Hamby, now a junior at Harvard University, was recruited to play soccer. She is currently ranked number two on her team and has won many honors including All-Ivy League Second-Team Honors and fourth in the Ivy League Helpers. As a high-profile soccer player, she has also made lasting contacts with donors and boosters.

“My connections at Harvard have helped me get my name out to soccer teams that are looking for potential new players,” Casscells-Hamby said. “Also, if my plan of becoming a professional soccer player does not come true, by being a student at Harvard, I also have many opportunities for jobs connected with boosters and donors.”

Equal Pay for Unequal Athletes

The issue of equality also comes into play if colleges were to pay their athletes. Should colleges pay all of their athletes or just those who have made significant contributions to the school? It would make more sense to pay just those who have made significant contributions, but that wouldn’t be fair to other athletes. Or should colleges vary pay with athletic performance? That puts an awful lot of pressure on student-athletes who are still developing athletic skills.

Additionally, let’s say a student attends a school because of his or her academic prowess. Does the university pay them any money because they have been working in genetics and have discovered something on a chromosome? No. If anything, their professor should get paid because they were in the professor’s class.

“A med student doesn’t get paid to study medicine; they themselves have to pay to do that,” Finnucan said. “So an athlete shouldn’t get paid to practice and work at getting better to become a professional. I think that the purpose of college is for an education. If you’re going to college to play sports to become a professional athlete, you should thank that college for providing you the exposure that they’ve already given to you.”