Science does not stop at the textbook. In the classrooms of Elmarie Mortimer, Bryan Moretz and Romina Jannotti, lessons are shaped not just by equations or lab procedures but by the years they spent conducting scientific research of their own. From nuclear physics to plant and cancer research to DNA repair, their experiences in the lab now fuel how they teach, mentor and inspire the next generation of scientists.

Cracking Nuclear Codes

face Science conference in Prague, Czech Republic.

Mortimer’s path to the classroom began in the lab with her PhD work in the nuclear research field at the Nuclear Atomic Energy Corporation in South Africa. She conducted research on the surface properties of metals and how they relate to nuclear war and the studying of particles inside nuclear reactors. With Mortimer’s heavy experience in nuclear research, she now teaches physics and tries to bring the process to her students while passing along the most important lessons she acquired through her exposure in research.

“Nature is full of surprises,” Mortimer said. “Just as you think you understand exactly what’s gonna happen, then something unexpected happens and you go, ‘OK, let’s keep going.’”

Science is not perfect the first time, and Mortimer reminds her students that she has learned from her failure and uses it as data. Using that mindset, she tells students that struggling with a problem set or lab does not mean they are bad at science, but instead serves as proof that they are learning how to think like scientists.

“It’s just looking for those connections and finding those parallels and seeing what you can get from that,” Mortimer said.

By connecting abstract equations to real-world applications, Mortimer encourages students to see physics as a way of how the world works. With real-life nuclear research, these experiences ended up creating long-lasting memories for Mortimer.

“Forty-eight hours of severe struggle and going off, I don’t know how many multiple cups of coffee, and about three hours of sleep and finally getting results that we had suspected (were) there, and the thrill of the system (behaving) the way you thought it might behave, it’s just fantastic,” Mortimer said.

Even with a lack of sleep, Mortimer recommends that research is worth it, especially to students who like solving puzzles and problems.

“(Doing research) is (when) you’ve been confronted with something unknown and it’s like solving a puzzle,” Mortimer said. “You get a little piece and sometimes it all fits together, and sometimes it takes time to get it to the point where it fits together.”

Small Stepping Stones

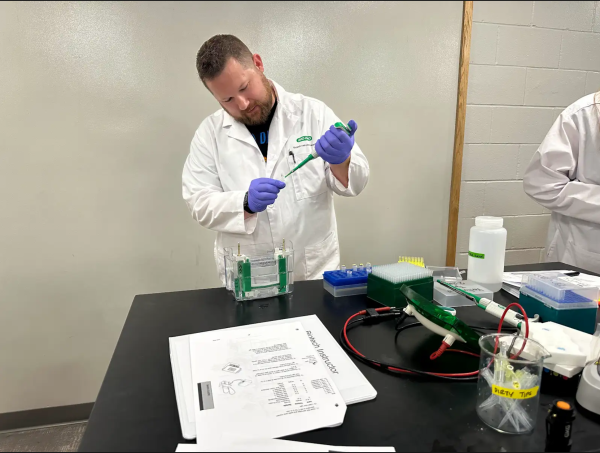

For Moretz, biology is all about patterns and connections. His multiple backgrounds in lab science and engineering give him a technical edge, but he always ties concepts back to their practical use. With Moretz working as an animal care technician, he was tasked with taking care of mice that were being tested on for cancer research and frogs used to study mutations. Moretz was also a student research assistant whose research focused on drought-resistant plants.

“Drought-resistant plants were really cool, mainly because we knew that there was a real-world impact for that kind of stuff and the sense that we could possibly save lives,” Moretz said. “And so any sort of research that you’re doing, you always have this end goal of ‘I’m going to have this big accomplishment.’”

Whether it is discussing ecosystems or cell biology, Moretz pushes his students to build resilience, even if they do cut-and-dry procedures.

“A lot of times I like to see them struggle because it means that they’re going through that process of science … and again, it might not work out as they expected, but that’s just part of science,” Moretz said. “We are so used to everything working right the first time, and we give up too easily, and so being able to have that resilience is important as a scientist.”

Moretz emphasizes that no matter what type of data or how experiments end up, small work adds up to big results.

“We don’t really pay attention to or see the end goal,” Moretz said. “We don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Emphasizing that resilience is key in research and in STEM overall, Moretz encourages his students not to give up if results do not go their way, as in the end, they are learning regardless.

Moretz recommends research to students as something that teaches you what works and what does not work and allows students to investigate anything, even if it is something personal to the student and not a panel.

DNA and Discovery

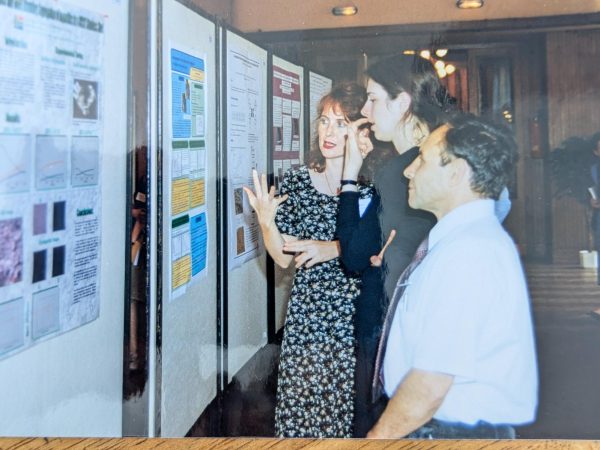

Before Jannotti began teaching chemistry, she earned her PhD from Stony Brook University, with her research focused on mitochondrial DNA repair, where she helped uncover the role of ligase 3 in genome maintenance.

“DNA ligase is an enzyme that seals (the) end DNA,” Jannotti said. “If your DNA is circular, you must have a ligase, so the human genome has four different genes for ligase. I discovered that DNA ligase 3 was the one that was going to the mitochondria.”

That experience and discovery shaped Jannotti’s mentoring style. She taught students to write proposals, defend their choices and learn from mistakes — the same lessons she once practiced in graduate school.

“Be honest, be constructive, but don’t be nasty,” Jannotti said.

What Jannotti tries best to do with her students is emulate what she went through.

“I like the idea that you don’t just get feedback from your instructor, but you get feedback from everybody around you,” Jannotti said. “And the idea that (with) feedback, you could tell someone something very honest without being nasty, it’s all in the name of making the work better.”

The benefits of research extend beyond lab skills. Jannotti emphasizes that it teaches critical thinking, problem solving and communication.

“It teaches you to think on your feet … to pose a question, and if the answer is still no, that’s still valid information,” Jannotti said.

Cure for Curiosity

As Jannotti used to tell her Independent Research and Design class, the first step is always asking the right question. For students, getting started in research is often a matter of taking initiative.

“Whatever you can, whenever you can,” Jannotti said.

She recommends looking at programs over the summer, such as UF’s Precollegiate Education and Training program, where students work with professors on ongoing projects. Networking is key.

“If you have a school around the corner and your sister is doing research in that lab … ask, ‘Can I stop by on a Saturday and watch what you’re doing? Can I be your tech?’” Jannotti said.

Even small opportunities can give students hands-on experience and open doors to larger projects. The benefits of research extend beyond lab skills.

Research can even teach students more than just information; it builds experience.

“I remember being in the lab. I would wake my husband up at 2:00-3:00 in the morning and I would say to him, ‘I have to go develop some film,’” Jannotti said. “And sometimes there would be a blizzard outside and he’d be driving me to the lab … I would go to the lab at 2:00 in the morning and half of my lab would be there. They would be playing poker (while) doing their experiments. We also back then were very tight.”

Students learn to adapt, be flexible and analyze results even when experiments do not go as planned.

“Take advantage of every opportunity and be open-minded, no matter how big or small the opportunity is, because it will open more doors for students than students think and students will most definitely learn more,” Moretz said. “That small work adds up to big results.”

Moretz emphasizes that even though he does not have a green thumb, he still fondly remembers working with plants and coming in every day to measure their growth.

Even though one of her favorite memories includes a lack of sleep, Mortimer emphasizes that getting into research is not just all work. Research can benefit students who just want to help out for the good of society as well as those who do it just for enjoyment.

“It shapes the way I view life,” Mortimer said.

Without her professor encouraging her to apply and take risks for research and without her watching “Advance to Ground Zero,” which got her into nuclear research, Mortimer might not have 29 publications to her name. Research does not have to be a student setting out to solve global problems but can be as simple as getting inspired by a movie.

“There’s never an end to research,” Mortimer said.