Sign language has existed for thousands of years. However, up until the mid-20th century, in America it was considered “broken English,” a mode of communication that was less sophisticated than the spoken tongue.

Zulma Santiago-Zayas, Professor of American Sign Language and Deaf Culture at the University of Florida, was born hearing in Puerto Rico but was deaf by the age of two and a half. She said that growing up, her teachers would hit her when she used sign language, and it wasn’t until she moved to the United States in the 1970’s that she learned and was allowed to use American Sign Language (ASL).

In fact, contrary to popular belief, ASL is not the gesture form of English; it is its own real language with regional dialects, tones, slang and even historically offensive slurs.

First, people often wonder why sign language interpreters use such intense facial expressions, and according to The Atlantic, they are used for grammatical purposes. For example, when signing a verb, squinting one’s eyes adds the adverbial clause “a little bit” to alter the meaning. Likewise, movements and expressions are also used to communicate various tones and emotions.

“When you are speaking, you don’t want to sound monotone,” Santiago-Zayas said. “It’s the same concept.”

Like spoken languages, there are also regional dialects in ASL; for example, Santiago-Zayas said that people from New York and California sign quicker than people from Florida. One of the biggest dialects of ASL is Black American Sign Language (BASL), which emerged largely because of segregation during Jim Crow. According to Splinter, an online political news organization, “phrases like “what’s up” and “my bad” are signed differently in BASL, which tends to be more expressive in nature than mainstream ASL.” Like in English, code-switching, the process of switching dialects depending on the person one is interacting with, also exists, as African Americans often use BASL amongst themselves and mainstream ASL otherwise.

ASL also has its own slang, and similar to English, the increased push for politically correct language has diffused to ASL. Handspeak.com, an online resource to help people learn sign language, explains that “kissfist,” which is signed by literally kissing one’s fist, means to really love someone or something, and “accept hard” is used to say ‘suck it up.’

Beginning in the mid-1990’s, many signs for countries — particularly Asian countries — were changed to be more culturally sensitive. According to the Baltimore Sun, the old way to sign ‘Japanese’ was to put the pinky finger next to one’s eyes, twist it and bring the hand back out, which goes back to historically stereotyping the Japanese as having slanted eyes. Similarly, to sign ‘Chinese’ used to be to shape the hand into a ‘C’ around the eye for the same reason. These signs, and others — including the signs for Jewish, homosexual, and African American — have since been replaced; Japanese is now communicated by forming the silhouette of the island of Japan.

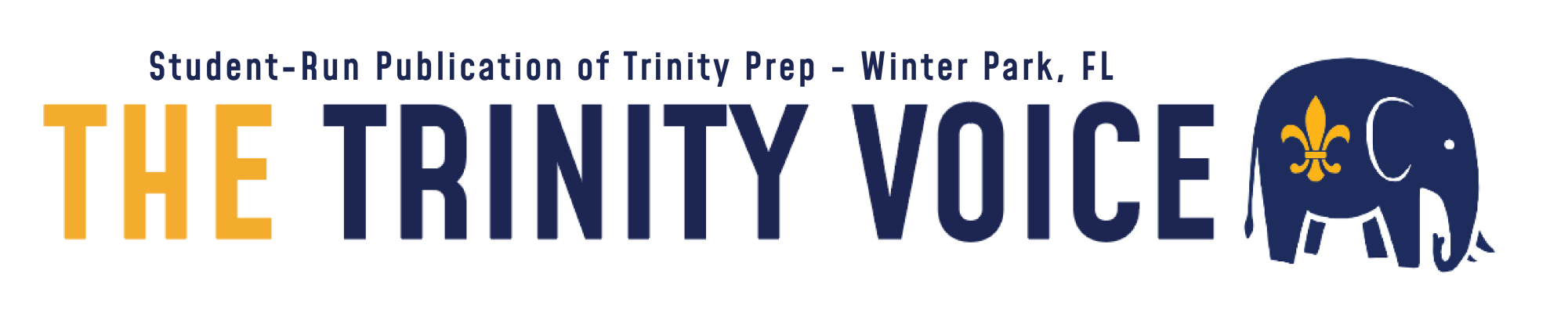

Furthermore, ASL is not the only sign language. WorldAtlas says there are about 300 different sign languages around the world, and even countries like the US and the UK that both use English have different sign langauges. World language teacher Courtney Zsitek uses ASL at the intermediate level, but it wasn’t until she traveled to Spain that she realized how different sign languages around the world are.

“I tried to join the conversation and realized that there are not that many similarities between American Sign Language and Spanish Sign Language,” Zsitek said.

Finally, one of the most influential events to happen to the Deaf community was the passing of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. The ADA requires that people with communication disabilities be supplied ways to communicate effectively, which for the Deaf might mean providing an interpreter or closed captioning.

Santiago-Zayas said that the ADA has helped her immensely in the work-place, and in general it has made her less reliant on her husband as an interpreter.

“I experienced growing up without the ADA,” Santiago-Zayas said. “Until the 1990’s, during that time I was working without an interpreter for the weekly meetings. Once the ADA was established, they realized I needed an interpreter.”

However, the ADA is not without its faults. In 2017 during Hurricane Irma, a sign language interpreter at a press conference in Manatee County, Fla. went rogue and, as stated by the New York Times, “warned of pizza and bear monster.” The interpreter, Marshall Greene, claimed his skills were not advanced enough for the situation; either way, the Deaf community was at a disadvantage.

Yet, despite historical challenges, ASL is thriving and is becoming the sign of the times.