In the midst of highly-achieving people all gathered at the intensive college prep environment of Trinity Prep, either you are a perfectionist or know someone who is.

Although on the outside, perfectionism looks like the ideal model to success, underneath reveals a system that ensnares its victim in a perpetual cycle of “never enough.”

“[Perfectionism] is the idea that ‘everything’s going to be perfect or that I have to be perfect,’” therapist Ana Martinez said. “Anything less than that is failure and unacceptable. It is an all-or-nothing mentality.”

While society associates perfectionism with productiveness, accomplishment and success. Like any behavior, too much of it can have the opposite effect.

“It can be healthy, it can drive you to the next step, but there’s a fine line,” Martinez said. “If you notice that ‘I have no time for anything else, because I have to get this done and if I don’t get this done, I’m a failure.’ Then that perfectionism might be costing you your own mental health. It’s one of those things that a lot of people don’t pay attention to until it’s having an impact.”

It becomes maladaptive (or unhealthy) perfectionism when goals become too unrealistic, standards too high, and when all that matters is accomplishing the next step and anything short of achievement becomes a testament to insufficiency.

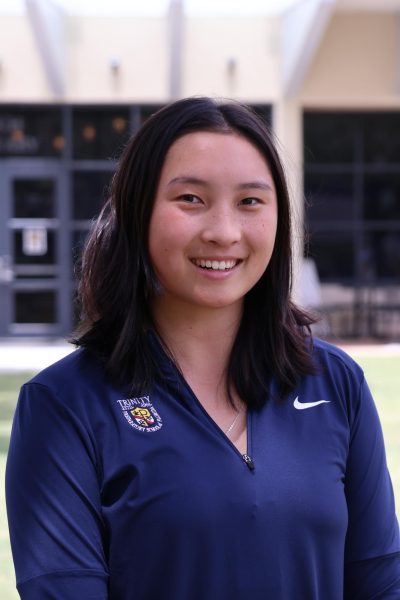

“Perfectionists, we always want the best … You’re never going to be satisfied with what you have right now,” junior Hannah Wang said. “You always want more than what you’re giving.”

According to the website Newport Academy, between 25-30% of teens suffer from maladaptive perfectionism. Most develop perfectionistic tendencies in adolescence, often when high scores and achievements are prioritized as the only source of validation a child receives at home. The desire for that validation is internalized and fear of failure becomes the foundation of perfectionism.

“It’s a sickly feeling that just stays with me the whole day,” Wang said. “You fixate on it for so long, it was there in 6th grade, it won’t leave again. It destroys my confidence. The next time I’m going to be triple-checking all my answers. I can still function, but it never leaves my mind entirely until I prove myself.”

Some eventually find that the mentality that previously allowed them to accomplish all these things is becoming parasitic as the stress accumulates in the highly competitive school environment.

“Being a perfectionist, it’s not glamorous at all,” Wang said. “Being a perfectionist is actually staying up late. There was a time I actually got so stressed that I started breaking out and my hair started falling out. There are physical ramifications of being stressed from this environment. It is deteriorating your mental and physical health. It ruins your experiences outside of school, who you are and your ability to have fun.”

Perfectionism consumes the person with constant pressure to rise to the top, so far that it becomes an isolating experience in which even friends become a reminder of competition.

“In popular culture, the idea of perfectionism is super high functioning and competent,” Co-author of “The Anxious Perfectionist” Clarissa Ong, Ph.D., said. “In reality, there’s this sense of loneliness … When you’re always trying to be better than someone, by definition, you cannot connect with that person because you’re always trying to be at a different level.”

Many perfectionists experience isolation where, even after reaching the top, they feel disconnected and empty.

“You had your experience with friends. But once you get there, you’re all alone,” Wang said. “It’s like the King of the Hill. You push other people off to get to the top, and once you’re there, what do you have?”

The relentless pressure to climb higher often leads to a point where perfectionists stop trying new things. Some might even succumb to inaction, paralyzed by their own overwhelming standards.

“As it intensifies it can even prevent you from trying things,” Martinez said. “‘Why will I try if I know I’m not going to get it? Why would I even do this if I know that other person has better qualifications?’ Then you are left with ‘I’m not good at anything. Why do I even try?’”

In trying to excel, they sacrifice various areas of their life — friends, family and their wellbeing — all to satisfy their constant perfectionistic needs.

“It’s a hamster on the wheel; there’s never a break,” therapist Diana Garcia said. “Anything to a certain degree you can only do for so long. Your body and mind might eventually show signs that you’re drained or overwhelmed. You make decisions fully based on external validation versus truly being driven by your values.”

Especially among students, many are willing to put aside their wellbeing for academic success, rationalizing that once they move past the goal of college, everything will be okay. So they continue to let perfectionism drive them, not realizing that many others have tried and failed.

“With perfectionism, the person likes this part of them,” Co-author of “The Anxious Perfectionist” Michael Twohig, Ph.D., said. “They usually come in suffering from the consequences of their perfectionism. I have clients who are 16 and 60 telling the same story … The truth is whatever you’re getting with this pattern of behavior is what you’re going to get in the future. By finding a healthy way to live now, you will enjoy a healthy life later.”

Perfectionism is not inherently bad. Being aware of where the line between healthy and unhealthy is can allow people to understand where their own limits lie and how to maneuver around the traps of perfectionism. Awareness comes through constant reflection of one’s own actions and being open about different strategies of support.

“We are a very individualistic society, a lot of people want to do it on their own,” Martinez said. “I ask them: ‘if you’re succeeding, you’re doing it, but at what cost? How is your mental, physical and emotional health? Is there anything that would make it better and why not use that resource? How much more would you be able to accomplish or how much better would you feel?’”

Defining values can shape the way a person approaches their goal. Values are completely in their control and provide an applicable approach to any situation as they do not revolve specific outcomes rather, a way of doing. Establishing these value-driven goals will prevent people from blindly following a path simply because society labels it as the route for success.

Prioritizing certain tasks can accomplish the very same goals but without the pressures of being perfect in every situation. Establishing self-compassion and empathy leads to a flexible version of perfectionism in a growth mindset where curiosity is the driving force.

“Growth mindset is striving for excellence,” Martinez said. “[There is] this desire to learn, this desire to grow, this motivation to improve. The fear may still be there, but the motivation to grow, to improve is so much bigger.”

Although society generally prizes all forms of perfectionism, schools can be an external support of healthy perfectionism by becoming more cognizant of the maladaptive side.

“Schools or work benefit from people going above and beyond, that comes back to [perfectionism] being reinforced,” Garcia said. “but this goes back to the role of schools, whether a trusted teacher, mentor or counselor would help students notice when they’re starting to go overboard.”

Twohig was the grad teacher who helped Ong realize the excessive efforts she poured into her studies in psychology. He dared her to give less effort and aim for a B grade. Ong discovered that even with significantly less effort, she still received the same A grade as she had previously without the extra hours of work. Twohig’s help in her own perfectionistic tendencies led to their eventual collaboration in writing “The Anxious Perfectionist” — a book for managing perfectionism-driven anxiety.

Despite all the support of teachers, books and friends and family, the ultimate decision to live a healthy, fulfilling life comes from within. While maladaptive perfectionism may seem like the only option in face of all the obstacles and goals to surmount, one can choose to mold their perfectionism away from a fear of failure into a desire for growth.

“Ultimately taking care of your health is not a chapter of your life, it should be an ongoing thing,” Martinez said. “What better way or what better time to start than when you’re young, so that when you go into whatever you do next, you can bring those right along.”