“People on top of a mountain did not fall there.”

This year, The Trinity Voice’s Copy Editor, Noopur Ranganathan presents a series of insightful interviews with pioneers who dared to dream big and changed the world.

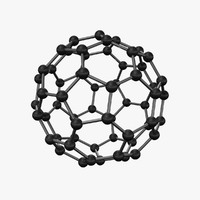

It was surreal: going to meet Sir Harold Kroto in person at the David Lawrence Convention Hall in Pittsburg. He is the 1996 co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. Until a few years ago, there were two known forms of pure carbon: graphite and diamond. Thanks to Sir Kroto and his scientist colleagues, we now have a third – C60 Buckminsterfullerene or the Bucky Ball C60.

The doors opened and in came a smiling, cheerful and distinguished scientist with a very sophisticated English accent. Although a Fellow of the Royal Society of London with many prestigious awards such as the Hewlett Packard Euro Physics Prize (shared 1994), the Faraday Award (2001) and the Copley Medal (2004), Sir Kroto was extremely down-to-earth. Born in Cambridgeshire, England, he attended the Bolton School in Lancashire. With an early interest in chemistry, physics and mathematics, he went on to attend the University of Sheffield and earned a Ph.D. in Molecular Spectroscopy.

“Atoms are the basic building blocks of matter that make up our world,” Kroto said. “A table, the water we drink, the air we breathe and even we, humans, are made up of atoms. Each atom has the properties of the element it belongs to.”

As chemistry suggests, there are 118 known elements which combine to form chemical compounds. However, there are a few exceptions that exist in the uncombined state.

“Carbon is one such element that exists in its pure state,” he said. “When atoms of carbon bond in different ways such that the element is structurally modified, they form ‘allotropes’ (different structural forms of the same element) of carbon. For example, when carbon atoms are bonded together in a unique tetrahedral arrangement, they form what every girl loves – Diamonds.”

Bucky Ball C60, Kroto’s latest discovery, is one such exception. It is an allotrope of carbon, where the atoms are bonded in spherical or ellipsoidal formations.

The name of the invention stems from its geometric shapes.

“Buckminsterfullerene is named after the American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes had a similar structure,” Kroto said. “The sphere-like molecule that looks like a football was named C60 Buckminsterfullerene or Bucky Ball C60 for short. ”

The discovery of C60 set off an explosion of research among chemists, physicists and materials scientists. Its unique structure absorbs large numbers of hydrogen atoms without disrupting the buckyball structure. This provides an efficient hydrogen storage medium that could develop fuel batteries for non-polluting automobiles. Furthermore, these unusual molecules have extraordinary chemical and physical properties. They react with elements from across the periodic table that provide novel opportunities in areas of optical devices, chemical sensors, chemical separation devices, electrochemical applications, drug delivery systems and polymers.

While explaining how it all began, Sir Kroto narrated how he and his colleagues, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley, came together to study carbon clusters due to Sir Kroto’s interest in carbon-rich red giant stars in space. After a series of experiments that generated carbon clusters, they discovered a sphere-like molecule that dominated the spectrum under various conditions. Thus the discovery of the molecule made up of 60 carbon atoms that looked like a soccer ball was completely serendipitous.

Sir Kroto encourages students to always investigate questions that interest them and advises them to follow through.

“Scientific discovery is often serendipitous,” he said. “You will never know what you bump into, but the journey is well worth it.”

He further adds that science is about truth and evidence and children should be encouraged to question and to doubt, in order to seek out the truth. He believes that teachers are relevant and important even in this era of Google, YouTube and Wikipedia, as they have the art of creating enthusiasm in students and encouraging their creative gifts. Kroto concluded with a remark in favor of fundamental science: “Not all those who wander are lost.”