If a Trinity student were asked where the most racial violence occurred in the twentieth century, they would probably say somewhere in the Deep South, like Alabama or Mississippi. However, as much as Florida has tried to cover up its past by portraying the state as a touristy, beachy paradise with progressive and modern cities, it doesn’t take away from the fact that Florida has a deep history of racism.

February is Black History Month, and as necessary as it is to celebrate the progress of people like Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., it is just as important to learn about the heroes of our own community and the disturbing situations that African Americans faced in Central Florida.

The Ocoee Massacre (1920) — 29 minutes from Trinity

Although the Fifteenth Amendment granted black men the right to vote and the Nineteenth Amendment women, most states in the South prohibited African Americans from voting by using grandfather clauses, literacy tests and/or poll taxes.

On election day of 1920 in Ocoee, Florida, a wealthy black man named Mose Norman tried to vote but was denied for not paying his poll tax.

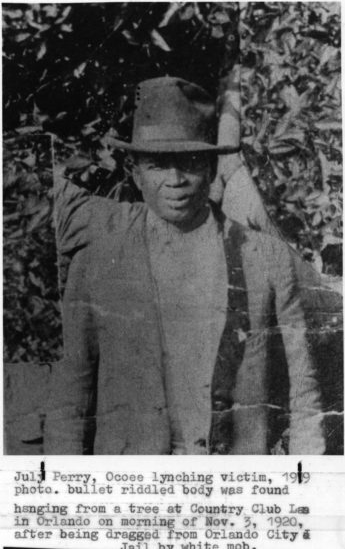

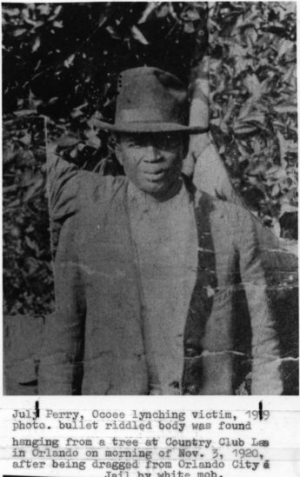

Later that night, a mob of white men, including some Klansmen, stormed into July Perry’s house in search of Norman. Perry was another prominent African American man from Ocoee, who fled the house and hid in a cane field. Once he was found, he was arrested and taken to the Orange County Jail.

The next day, a mob kidnapped Perry and hanged him from a tree in Orlando. In addition to this, 25 homes and two churches belonging to African Americans were burned, and more than 30 African Americans were murdered. The massacre forced the black population to flee Ocoee, where not a single black person would return to live until 1981—61 years later.

The Groveland four (1949) — 48 minutes from Trinity

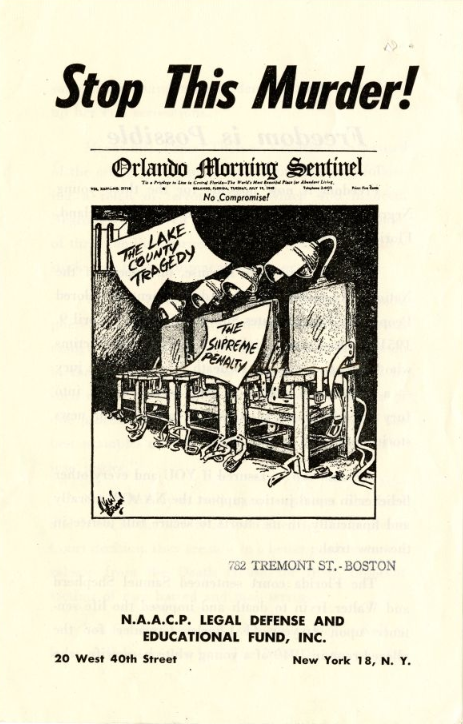

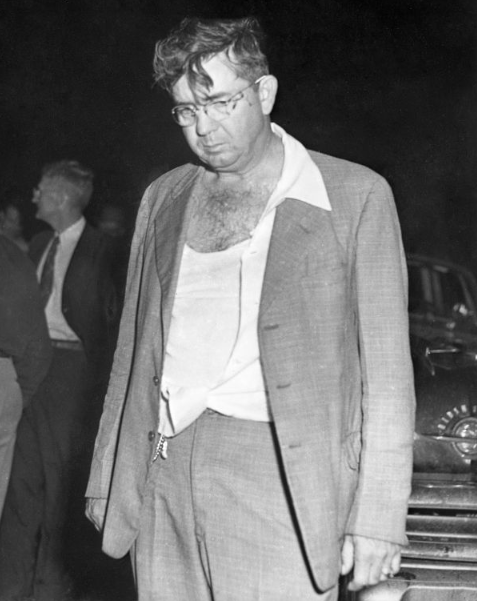

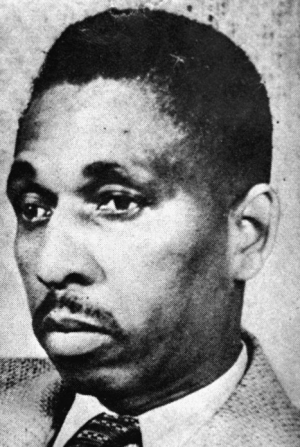

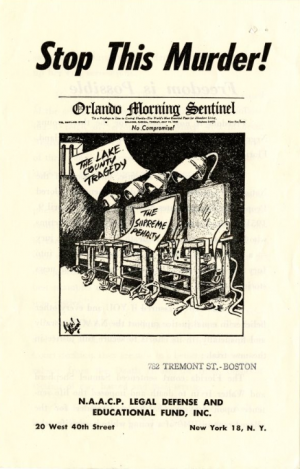

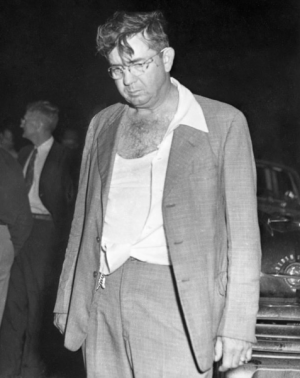

On July 16, 1949, in Lake County, Florida, four black mens’ lives were changed forever. Ernest Thomas, Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin were accused of raping Norma Padgett, a white woman, and assaulting her husband Willie after the couple’s car broke down. Greenlee, Shepherd and Irvin were taken to the county jail, while Thomas was captured a week later and killed by Sheriff Willis McCall.

The three remaining men were convicted of rape by an all white jury, despite medical evidence that suggested that Padgett had not been not raped. Shepherd and Irvin were given the death sentence, and Greenlee, who was only 16-years-old, was given life in prison.

After the NAACP took Shepherd’s and Irvin’s appeals to the Supreme Court, the ruling was overturned in 1950. However in 1951, when McCall was transporting the two men back to Lake County, he shot them. McCall was never tried, claiming that they had attacked him, even though they were handcuffed in the backseat. Shepherd died, but Irvin survived to reveal that the sheriff forced them out of the car and shot them on the ground.

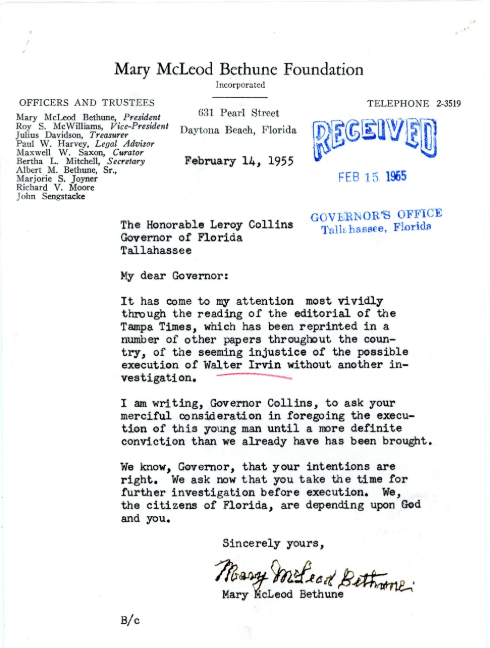

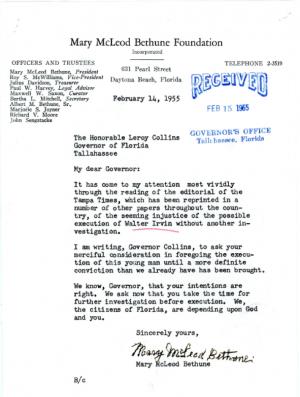

Irvin was later convicted of rape a second time and sentenced to death, but Governor LeRoy Collins limited the conviction to life in prison in 1955.

In 2017, the Florida Legislature formally apologized for how the case was handled, and the Grovlenad Four were pardoned in 2019.

Sheriff McCall was elected to five more terms until 1972.

The Murder of Harry T. Moore (1951) — 44 minutes from Trinity

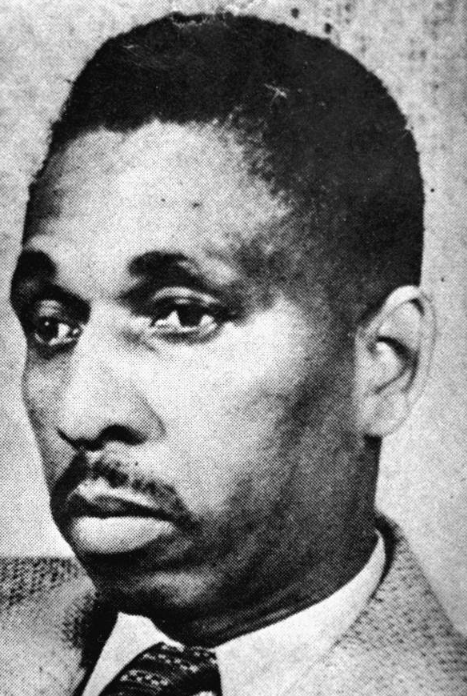

Harry T. Moore was a black man who lived in Florida with his wife Harriette and daughter Peaches. Moore was a very passionate activist for civil rights and founded the Brevard County NAACP.

He was heavily involved with the NAACP and turned his focus to police brutality and lynchings. From 1900 to 1930, Florida had the highest lynching rate in the U.S., compared to the size of the population, and 61 African Americans were lynched from 1921 to 1946.

Even today, many of the African Americans who were lynched around the country are still unknown. But despite these barriers, Moore investigated each lynching in Florida.

Moore also founded the Progressive Voters’ League and registered more than 116,000 black voters by 1950, which alarmed white politicians. Furthermore, he helped uncover evidence in the Groveland Four case that revealed the four men accused had been beaten.

The Ku Klux Klan, white supremacests and politicians were threatened by Moore and the progress he was making by registering black voters and digging into the violent past of white supremacy. Harriette and Harry Moore were murdered on Christmas Day of 1951 after a bomb went off under the floorboards of their house, suspected to have been placed there by the Ku Klux Klan.

They lived in Mims, Florida but died in Sanford, and the murders have yet to be solved. Moore’s death sparked numerous protests and memorial gatherings, as he was the first official in the NAACP to be killed in the Civil Rights Movement.

The Trinity Perspective

Of 228 Trinity upper school students surveyed, 75 percent of them had never heard of the Groveland Four, and only 12.7 percent of the students knew of Harry T. Moore, one of the most influential Floridians in the struggle for civil rights.

Social Science teacher Robin Grenz thinks this is due to the lack of local history taught in social studies classes.

“It’s not in textbooks,” Grenz said. “So unless you make an effort to go out and find out about those things, you’re not going to necessarily know them.”

It is hard to come to terms with the fact that our community’s ancestors denied black people their constitutional right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. However, in order to make social progress, it is crucial to learn who we are and what brought us to this place in history. Understanding local history is so valuable because it helps us to be on the right side of history and not to make the same fatal mistakes that our ancestors did.

“That’s why we study history,” Grenz said. “It’s about building connections, it’s about understanding who we are, looking at mistakes or controversial topics and trying to move in a more positive direction or understand the perspectives of our diverse population.”