Before computers, college applications were filled out by hand or typewriter and sent to colleges via fax or snail mail. Now, the college process is becoming more automated than ever. With the advent of the Common Application, Match by Concourse and SCOIR, the college process is moving in a more data-driven direction. By adopting a more impersonal approach, these platforms are sending a message to college counselors and students: a student’s grade point average (GPA) and standardized test score is the most important piece of their application. This makes it more likely for a student to gamify the college process and compare themselves to their peers on the grounds of test scores and GPA.

The common application, which seniors use to apply to most of their schools, is a single online college application form used by over 900 colleges and universities. Having a universal application to house all of the essays and information makes the application process more simple for students–but almost too simple.

“Students are applying to way too many schools,” Director of College Counseling Christine Grover said. “It’s too easy to just keep adding schools onto your common application.”

With more and more people applying to college, universities become more selective. With more applications to read, colleges are looking to standardized test scores and GPA to get immediate answers about their applicants and often discount essential information.

Another college network software, Scoir, is used by high schools nationwide – including Trinity. SCOIR has a new feature that uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) to predict a student’s likelihood of acceptance. However, SCOIR’s predictive chances only take into account standardized test scores and GPA. Reliance on standardized test scores and GPA to determine whether a student gets into a school only feeds into the idea that standardized test scores and GPA are all that a student brings to the table.

“I hate the AI predictive chance,” Grover said. “It doesn’t see the factors we see…The AI predictor was showing that our students had a good chance of getting into Georgia Tech. It did not factor in the fact that we are out of state and they are taking a much smaller portion out of state… I’ve asked SCOIR to turn [the AI feature] off because I find their AI to be detrimental to students.”

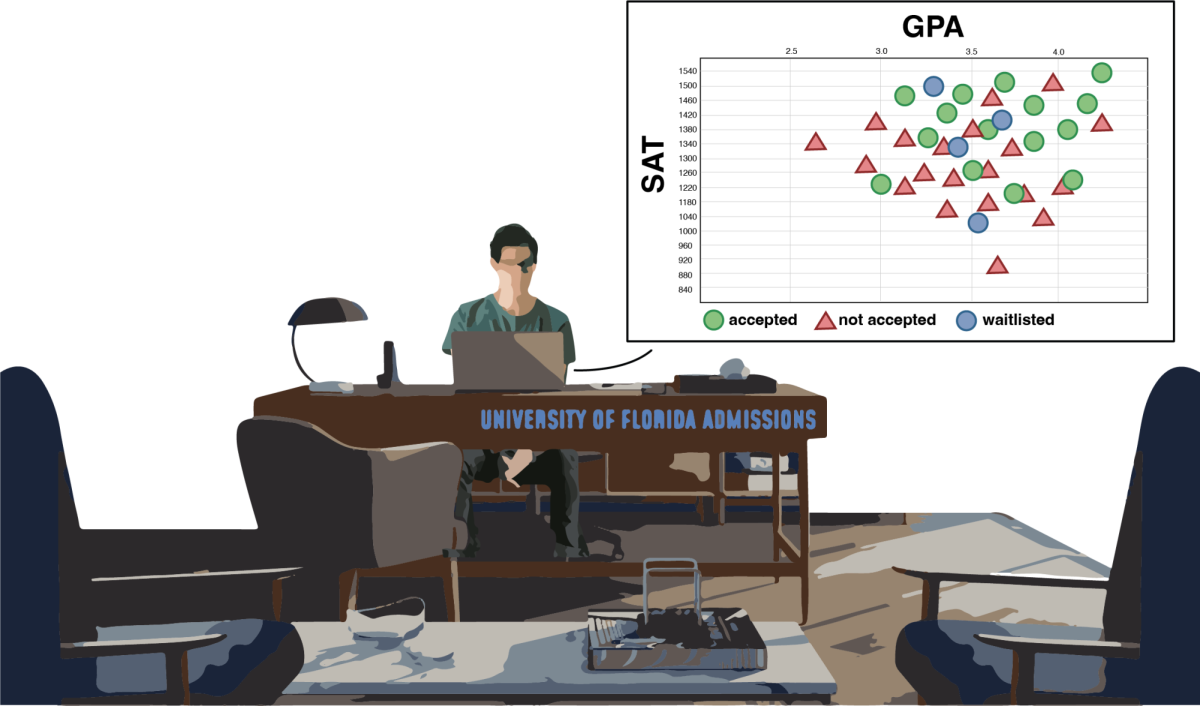

In addition to the AI predictor, each student has access to a scattergram that shows the standardized test score and grade point average (GPA) of every applicant from their school to every college and the outcome of their application. The graph can be used by college counselors to help a student make two decisions: whether to apply and in the case that they do, whether they should send their scores. Looking at the scattergram and seeing their dot, on the lower end of the graph, can be discouraging for students.

More concerningly, Trinity students have turned SCOIR scattergrams into a guessing game, trying to identify the anonymous dot on the graph. Because of this, seniors have become increasingly secretive about their test scores and GPA.

“They’ll try to guess who it is on the scattergram or they’ll try to figure out…who they need to beat out,” Associate Director of College Counseling, Maya Lupa said.

The fear of sharing too much or sharing too little is often on the minds of Trinity seniors, and SCOIR scattergrams only exacerbate the issue.

“When you’re sharing that type of number, there is such a high level of anxiety around it,” senior Zara Kalmanson said. “It’s almost like your social security number.”

Trinity has adopted another software, Match by Concourse, which is a tool colleges can use to offer an immediate acceptance to their university. At the beginning of the year, counselors advised Trinity students to give Match by Concourse simple information about themselves. Weeks later, Trinity seniors were offered acceptance into universities they never applied to based on surface-level information.

“Match by Concourse never sees a student’s name,” Grover said. They’re putting in their test scores… GPA, and the courses they took.”

While it might be nice to have some guaranteed acceptances from any college, there is more to an applicant than their statistics. Extracurricular activities and essays show more of who an applicant is and what they can bring to the university.

“Even my brightest students…have a hard time coming in to talk to me or to move forward with the application process because they are questioning themselves or the things that they’ve done because of this comparison,” Lupa said.

Data-driven features like these only generate competition. Trying to control the unpredictability of college applications seems to only fuel students to compete against each other. No one can confidently determine whether they will be accepted or denied from any college, but students and AI can now act like they can.

While these tools can be used to fuel competition, when used appropriately, these systems have the power to benefit the application process.

SCOIR scattergrams, for instance, can be used as a tool to advise their students, without actually showing students their peers’ data. This can easily be achieved by putting the scattergram into perspective and realizing that most colleges take a wider view of the applicant. Students must remind themselves that the college application process is a deeply unreliable system, and students are more than a dot on a graph.