There’s a Chinese proverb that says 一个可以吞下侮辱的人是一个男人 or “One who can swallow an insult is a man.” In the light of the East Asian hate crimes this past year, this phrase represents the silence and backlash that Asian Americans have taken.

Inny Kim, a long-term sub for social science at Trinity Prep, was standing in the checkout line at Costco when she remembered she had forgotten to buy some eggs. She dropped out of the line and ran towards the produce section when she heard someone call out, “Run back to Asia while you’re at it.”

Like Kim, another Asian American who asked to remain anonymous, was shopping at Walmart at the beginning of the pandemic last year when an old man stopped her. Rather than introduce himself, he started shouting racial slurs and eventually, coughed on her before walking away.

These two experiences make up only a fraction of the number of hate crimes against Asian Americans this past year. The xenophobia towards China has become the fuel for the ongoing racism against Asians in America. But ever since the Atlanta spa shooting on March 16, Asian-American racism is finally being discussed on a national level.

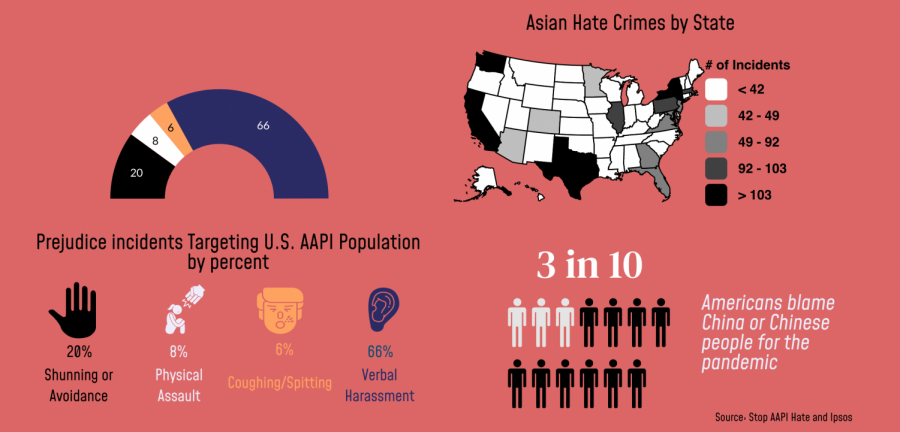

A study done by Stop Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Hate revealed that, despite an overall decline in the total number of hate crimes since the pandemic began, there has been a 150% increase in hate crimes against Asian-Americans in 2019-2020 in major cities of the U.S. alone. However, the 3,800 incidents that were reported to the AAPI do not come close to representing the true extent of these hate crimes.

“What our data shows is that upwards of 2 million AAPIs have experienced these hate incidents since COVID-19 started,” Karthick Ramakrishnan, the founder of Stop AAPI Hate told NBC. “But a very small fraction of them have reported to community hotlines, and an even smaller proportion have been established by law enforcement authorities as hate crimes.”

A survey at the end of last March by Stop AAPI Hate found that roughly 1 in 10 Asian Americans has experienced a hate crime or incident just this past year. But the target for the majority of these hate crimes is not random either. The study found that out of the 3,800 cases, 68% of these hate crimes were reported by women. And it is not by accident either.

“How come a lot of white people think Asian women are approachable and that they represent the temptation?” said the anonymous speaker who was verbally harassed in Walmart “I think it’s the media that shapes Asian women into weaker and a more approachable group.”

Women like Kim and the anonymous source believe that many people stereotype Asian women as docile and non-confrontational, thereby making them an easier target.

But these hate crimes didn’t just start with the COVID-19 myth. A long history of discrimination against Asians in America has largely been undermined by the “model minority myth.” The stereotype that paints Asian American immigrants as the minorities who made it or achieved the American Dream not only fails to recognize all Asian-Americans from all sides of the socioeconomic spectrum but also helps conceal the almost century-long racism in America.

Historical events like the Chinese Exclusion Act, where the United States barred immigration solely based on race, and Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 that incarcerated people under suspicion as enemies to inland internment camps, where a mass majority were Japanese, are representative of the racism towards Asians today. The model minority myth has always been used as a defense mechanism that does not give Asian-Americans the chance to fight back.

And similar to the SARS outbreak in 2003 where Asians were similarly discriminated against in Canada because of the false belief that “All Asians have SARS”, the COVID-19 Asian myth that has been backed by sayings like “the Chinese Virus” has only heightened this innate racism and given it backing for radical actions.

“There’s always been an acknowledgment of racial differences, and I don’t think it’s changed, the image that Asian-Americans have of an outsider,” Kim said.

But the victims of the COVID-19 Asian myth are not just those who have been subject to these hate crimes. It has affected every Asian American. Sophomore Tyler Principe who is part Vietnamese, has always taken pride in his Vietnamese culture. However, ever since the pandemic struck, he has been reluctant to reveal his Asian race as he would often hear racist jokes about COVID-19 and Asian Americans.

“I’m not afraid of how people would judge me,” Principe said, “but it’s the actions that could result from it that scare me.”

And the hatred does not account for age either. Kim’s 8-year-old son is the only Asian boy in his class. Kids at his school would make fun of him for his appearance and crack jokes about the COVID-19 pandemic and Asians.

“The other day he was looking in the mirror and said ‘Mom, I wish I had blue eyes’ and ‘Why do my eyes look like this?’” Kim said. “Seeing it through the eyes of my kids really breaks my heart. If it happens to me, that’s one thing. I can ignore … but for my kids, it’s a deeper struggle they have.”

In hopes of combating these issues, President Joe Biden proposed allocating $49.5 million dollars from the American Rescue plan to programs like AAPI. Additionally, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has created a whole agency initiative, whose responsibility it is to address and solve these hate crimes.

This department plans to address the misinformation on the media that has undermined these hate crimes by establishing an interactive hate crime page monitored by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to help give the public accurate information. Finally, the DOJ partnered with the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (NAPABA) to promote community outreach and interaction.

Kim and the anonymous speaker believe that the only solution is education. In her classroom, Kim brought foreign foods from Korea to share with her class. She said she was shocked to see the lack of knowledge her students had about Asian culture.

“I think part of it is you’ve got to stand up for yourself, you’ve got to stand up for your culture and help educate people around you about the differences,” Kim said. “You’ll see at the end of the day some similarities.”