Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes was found guilty of defrauding investors to her company, causing losses in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Her company promised a small device that would be able to run hundreds of medical diagnostic tests with a single drop of blood compared to the traditional intravenous blood draw. If it was possible, this would have had the potential to revolutionize the medical testing world, which is part of the reason why Holmes and her company were put in such a large media spotlight.

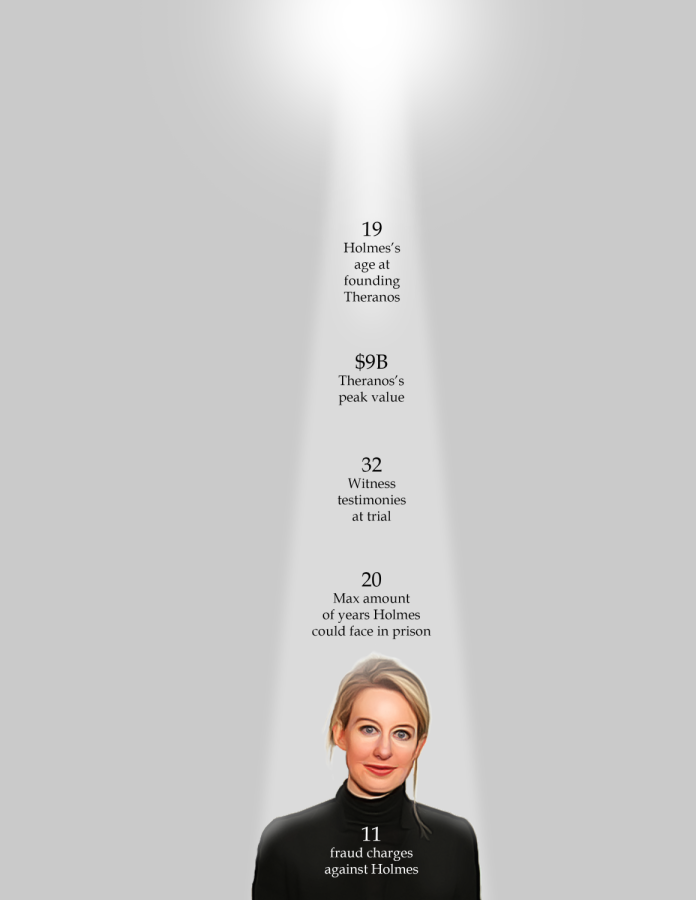

Holmes started her company, initially named Real-Time Cures, at 19 years old after dropping out of Stanford University. According to former dean of Harvard Medical School Dr. Jeffrey Flier in an interview with BBC News, he said that when speaking with Holmes in 2015, she did not seem to know much about her technology but seemed self-assured otherwise. Flier said that her lack of knowledge was odd coming from the CEO of the company, but he didn’t suspect anything fraudulent.

Computer science teacher Brenda Berube received her master’s degree in biomedical technology and management which led to her becoming a certified clinical laboratory scientist.

She explained that before a device like Theranos’ blood testing machine, named the “Edison,” could even receive its first drop of blood, many extremely controlled and precise experiments must be run to ensure that the machine worked as intended.

“You have to go through and make sure that somebody is checking the temperature in the room at the same time, checking the electrical current at the same time, [and] between each shift do the calibration,” Berube said.

In order to have her product eligible for human use, Holmes would have to subject the Edison through this testing on all 240 of its different tests, a process that Berube said was already tedious with just one test. But the Edison did not actually do 240 tests. According to USA Today, only 15 of the tests were actually conducted on the machine while the others were sent off to other laboratory equipment. Because Holmes did not share this information to investors, they were misled on how the product actually worked, leading to the multiple counts of investment fraud in the trial.

While Holmes was found guilty on four charges of defrauding investors, 11 total charges were brought against her in the 15 week trial. The charges that she was found not guilty on were relating to defrauding her patients. In addition to Berube’s experience in biomedical technology, she has also served as a DNA forensic expert witness. As part of her job, she advised lawyers on what kinds of questions they could ask relating to the forensic evidence and how to present that information to a jury. She explained that one of the difficulties of the Holmes trial was explaining both the familiar investment and business information and the complicated biomedical information to the jurors.

“It is difficult enough, in my experience, to have shared [the trial information] with lawyers, and think of the level of education and level of reading ability that they have,” Berube said. “So to be able to share [the trial information] with them compared to jurors of all different backgrounds, it’s very difficult.”

Berube also said that since the jury only found Holmes guilty of charges related to these more familiar financial issues, they may have been more comfortable and familiar with that information compared to the more complicated science-related charges.

According to Berube, the trial brings up the concern of what should and should not be shared by companies to the public versus stakeholders.

“My concern is that [when] you’re a CEO of a company, you can have privacy of your product…but you do have a responsibility to share that with your board or your stakeholders and people investing,” Berube said.

She also said that the public perception of the biomedical field is being altered by the trial, making it harder for people to trust these biomedical companies with their health. This skepticism and push for faster and easier medical testing devices is not a new concept. In 1988, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) were passed that dictate federal regulations of who can use different kinds of testing equipment. The most recent decisions CLIA has made are relating to COVID-19 testing, which is a subject that most people are eager to get involved in and understand because of its impact.

Berube said that while this case does bring many concerns to the general public about the biomedical testing industry, there may have also been some good things that came out of the trial.

“This is probably the first time ever that this field, I believe, has a public voice,” Berube said. “I think it is because of the general public trying to be educated on companies, and in vaccinations and approval processes.”