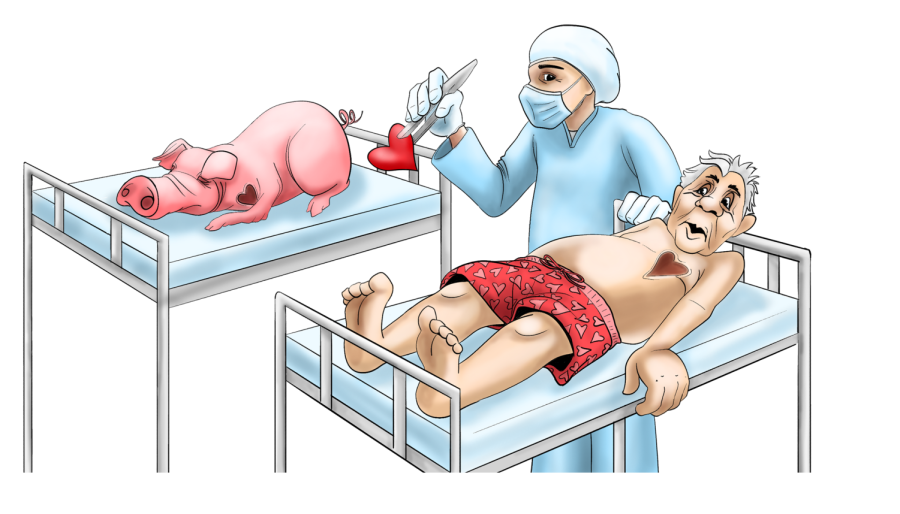

On Jan. 7, David Bennett became the first human to receive a pig heart. The heart had received 10 genetic modifications, including the removal of four pig genes and the addition of six human genes. According to Medical News Today, this transplant was done by faculty from the University of Maryland School of Medicine under emergency FDA authorization for the procedure.

Bennett’s revolutionary transplant is also known as a xenotransplant, which is the process of transplanting nonhuman organs, tissues or cells into humans. However, the idea of xenotransplantation has been around for centuries, dating back to the 17th century when Jean Baptiste Denis tried blood transfusions from animals to humans.

Despite having been around for so long, xenotransplantation is not widely practiced because it’s highly complex. It comes down to a challenge that exists in both regular and animal transplants, and that’s getting the body to accept the organ. In normal transplants, sometimes the body will identify the transplanted organ as alien and make antibodies to break it down. This is known as a “rejection” and causes the organ to have reduced function or even fail.

According to anatomy teacher Anthony Palumbo, xenotransplantation has an even higher risk of rejection. This is because xenotransplantation is essentially inserting a genetically foreign animal organ into the human body, so our own immune system is even more likely to acutely reject the organ, registering it as a threat and fighting against it as an invader.

However, Bennett’s transplant shows that through use of CRISPR gene editing and immunosuppressant medication, xenotransplantation can become a reality, which would have a great impact on science as a whole.

“[Xenotransplantation] opens up a brand new branch of science, gets more jobs, more research,” Palumbo said.

The reason this milestone is so significant is because it puts scientists closer to solving the worldwide organ and blood shortage.

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, as of October 2021, in the United States alone there were over 106,000 people on the waiting list who need an organ. Every 9 minutes, another person is added to the list, and every day, 17 people on the waiting list pass away waiting for an organ.

The United States is facing its worst blood shortage in a decade, according to the Red Cross. This organization supplies 40% of the nation’s blood supply, but a lack of donations has led to one in four hospitals missing the blood products they need.

However, once scientists reach a point where they can use gene editing technology to create animals that have any human organ or blood type, they can circumvent human donors entirely to create a more accessible future of organ donation.

Although xenotransplantation is a revolutionary medical invention, it still has a host of issues that need to be addressed, the first of which is xenogenic infections. These are infections that are transferred from an animal to a human through xenotransplantation. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) consultation on xenotransplantation-associated infectious risk, xenogenic infections could potentially lead to a wide variety of animal pathogens infecting humans. Furthermore, these animal borne diseases could also lead to serious complications for the transplantee due to the immunosuppressants they are taking.

“As a human race, we have not done well with animal disease,” Palumbo said. As a result, he thinks we shouldn’t try xenotransplantation and run the risk that it could create even worse zoonotic diseases.

Furthermore, xenotransplantation is also accompanied by a host of ethical concerns, especially from animal rights activists. By trading animal lives for human lives, many argue that scientists will not know where to draw the line and will end up exploiting animals without a useful purpose.

Though, according to ethics teacher Benjamin Gaddis, if the animal’s death serves a purpose in saving someone’s life through xenotransplantation, then it’s justified from both a utilitarian and self-preservation perspective.

“Which creates the greatest benefit, another pig or cow alive, or a human being that’s really adding to our society?” Gaddis said.

Even in the face of all its issues, if humanity uses the emerging science of xenotransplantation conservatively, it can solve the organ shortage plaguing the world without needlessly abusing animals.

“It comes up to this idea of purpose: are the animals being abused and raised just to provide organs, or do they get to be an animal until an organ is needed?” Gaddis said. “If we are driving this in such a way that these organs are here and these animals are also here, then let’s use them.”

*After the paper publication, David Bennett died two months following this transplant.