With claims of voter fraud and a slew of lawsuits, the election of 2020 was one for the history books. As ballots were counted––and recounted––the election was decided by a slim margin of only a couple hundred thousand votes in a few key states. Yet, despite this close result and heavy contentions from the opposition, in reality, Joe Biden won the popular vote over Donald Trump by nearly 5 million votes. No lawsuit can change the fact that he was clearly the candidate favored by the American people. That this election was as close as it was in spite of this margin reveals a clear flaw in our democracy: the Electoral College.

The Electoral College, as established in the Constitution, is the formal body that elects the President and Vice President of the United States. Among other reasons, it was created by our Founding Fathers out of fear of mob rule and in an attempt to consolidate power among an elite few. Our founders didn’t trust the masses to make an informed decision regarding the President and determined that it was best to leave the decision to an educated group of electors appointed by the states and given the power to vote independently.

However, this process has become antiquated for several reasons. In the late 1700s, it might be true that many people lacked the information needed to make an informed decision. But the nationalization of political parties and widespread access to the internet has eliminated the need for electors to make decisions for an uneducated populace. The vast majority of Americans have access to a variety of information at their fingertips or at least have a decent idea about what the candidate stands for, and the thought that they cannot make an educated decision is an insulting one.

Moreover, these electors are no longer independent of the states. Over time, the majority of states have enacted “winner-take-all” policies, in which each elector in a state votes in accordance with the results of their state’s popular vote. In fact, 33 states have passed laws punishing “faithless electors” who act contrary to this popular vote. In the other states, electors are not technically required to act how their state wishes, but still rarely act against it––only 165 people have as of 2016––as these electors are nominated in the first place by whichever party wins the popular vote in a particular state.

The constitutionality of these laws punishing faithless electors was challenged, but they were upheld in a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court last July. Essentially, while the practice of being a “faithless elector” is still legal, the court ruled that states have the right to punish these electors, preventing our flawed system from becoming any worse.

Maine and Nebraska are exceptions to this winner-take-all system. They’ve adopted what is known as the “district method” in which electoral votes can potentially be divided among candidates. In these states, two votes are awarded to whoever wins the state’s popular vote, while the other two are given to whoever wins each congressional district (there are two in Maine, and three in Nebraska).

Though it has its nuances, the system we have now, in theory, is just a convoluted popular vote; however, history has shown it doesn’t work that way. In 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016, a candidate won the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote, proving that this system doesn’t effectively capture the will of the people.

The origins of the Electoral College are also shrouded in racism, which seems to receive very little attention. It was a system created in the midst of widespread slavery and was a further implementation of the infamous Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted African Americans as three-fifths of a person when determining a state’s population.

James Madison knew the South would never agree to a direct election or popular vote because, excluding slaves, populations in Southern states were significantly smaller. Thus, with a popular vote, the South feared the North would have a disproportionate influence on politics. So, Madison created the Electoral College in which electors would be awarded by population size, a number, which as a result of the Three-Fifths Compromise, included slaves.

It may seem obvious, but it warrants being said: with all these antiquated reasons for the formation of the Electoral College, why does it still exist? Preserving such a system is illogical, racist and detrimental to our democracy, and it’s remarkable it has persisted as long as it has.

Those in favor of the Electoral College claim that it protects small states and ensures their voices are heard. To a certain extent, this claim is valid. Despite a larger number of electoral votes overall, California receives 1 vote for every 680,000 people whereas Wyoming receives 1 vote for every 190,000 people. Supporters argue that this ensures that smaller states are represented in government and that it prevents candidates from campaigning in only large cities, as they would if the Electoral College was abolished in favor of a national popular vote.

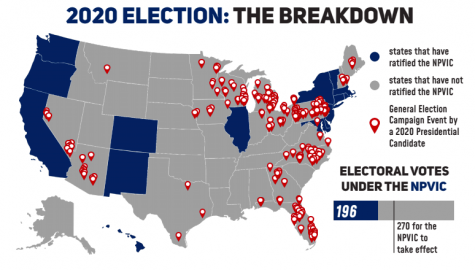

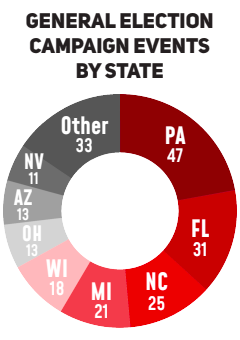

Yet, the way the Electoral College is set up, candidates only campaign in a small number of swing states, to begin with, and will rarely visit rural areas. In 2020 for example, 96% of presidential campaigning was done in just 12 battleground states. Thirty-three states (constituting much of rural America) and the District of Columbia received no visits at all, proving that these smaller, rural states are not as protected as proponents of the Electoral College may lead you to think. In theory, a candidate only needs to win the 11 states with most electors to earn 270 votes and win the presidency, regardless of how the other 39 states vote.

Even if the Electoral College did give smaller states more of a voice than they’d have in a national popular vote, it still restricts more voices on an individual level. To a Democrat in Alabama or a Republican in California, their votes don’t matter, as their states will simply award all their electors to the opposition party, regardless of their opinions. In a national popular vote, a vote in a swing state matters the same as a vote in a safe blue or red state.

While some may argue that it is best to simply reform the Electoral College and award votes via the “district method” as they do in Nebraska and Maine, this system is technically not proportional, and with the issue of gerrymandering––the manipulation of congressional district lines for political gain––estimates have shown this leaves even more margin for error than the current system. Thus, the best solution to our flawed system is simply a national popular vote. Though this may reduce some certainty in the outcome of elections as popular votes can be quite narrow, it’s the only way to guarantee everyone’s voices are heard.

Since the Electoral College is included in the Constitution, changing the system would need a Constitutional amendment, which would require a two-thirds majority vote from both houses of Congress. But, the Electoral College largely favors Republican candidates in close races, and with the partisan deadlock we see today, it is becoming increasingly unlikely this two-third majority could ever be reached.

Luckily, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact has proposed a workaround to this dilemma. This is an agreement between states that would bind each states’ delegates to whichever candidate wins the national popular vote. While the Constitution is clear that states must appoint electors, it never says how the states have to use them, which is why this could be effective.

Currently, the compact has been agreed upon by 15 states and the District of Columbia and encompasses 196 electoral votes. Once it reaches 270 electoral votes, it will take effect, and this will guarantee the presidency to whomever wins the popular vote, a true representation of the will of the people.

If the United States is to remain “the world’s greatest democracy,” or frankly come anywhere close, the Electoral College needs to be abolished. It’s racist, outdated and restricts the voices of the people. In a true democracy, everyone’s vote should matter, and only through replacing the Electoral College can this ever be achieved.