On Nov. 1, the Supreme Court signaled that there could be an end to the half-century long practice of affirmative action, race-conscious admissions, after hearing oral arguments on the case Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard College. The Petitioner of the case, SFFA, argued that by giving on-average low personal ratings to Asian applicants, and on-average high personal ratings to Black and Latino applicants, Harvard systematically racially discriminated against Asians.

To clarify, these ratings consisted of intangible factors taken from essays, recommendation letters, and interviews, but were found to be manipulated to impose a race penalty — Asian students aren’t really less personable.

Asian Discrimination

Using logistic regressions created by SFFA’s expert witnesses, it was found that the race penalty imposed on Asians is so significant, that if Asian applicants were treated as white applicants, their admit rates would be 9% higher. The racial preference given to other minorities is even greater than the Asian penalty as Asian applicants admit rates would increase “threefold” if they were treated like Latino applicants and “over fivefold” if they were treated like Black applicants.

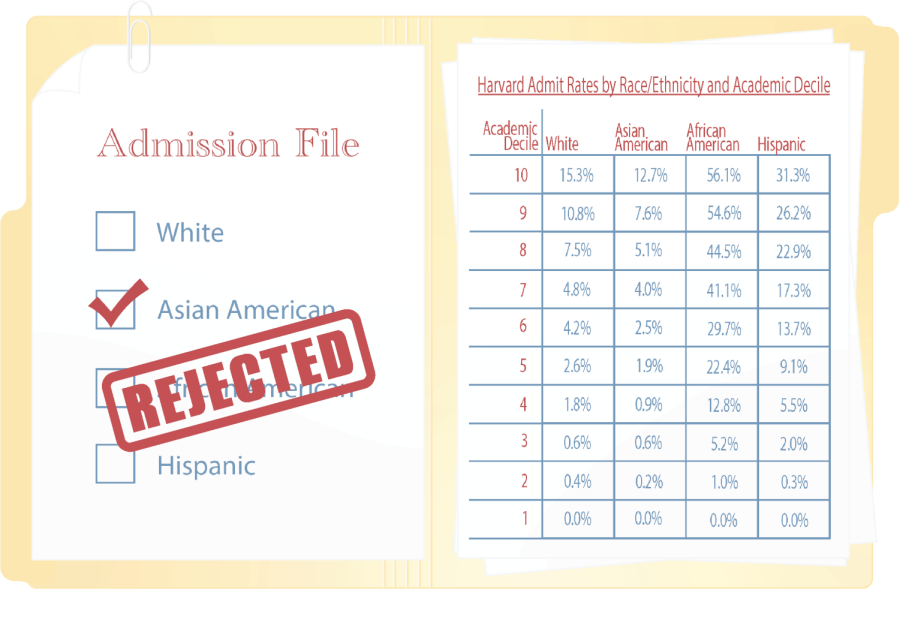

In their Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, SFFA found that based on academics (grades and test scores), Black applicants who ranked in the bottom 40th decile were as likely to gain admission to Harvard as Asian applicants who were in the top 10th decile (see graphic). Qualified Asian applicants are being passed up at a magnitude so large, that just checking off Black or Latino on an application has the same value, if not more, as an Asian student winning an academic national award.

It is commonly argued that college admissions is a holistic process, and that traditional academic metrics do not account for everything. However, a rebuttal expert report showed that when looking at non-academic metrics, excluding the discriminatory personal ratings, Asians made up the largest share by race in the top decile of non-academic metrics. It does not make sense why Asian applicants would be penalized when, on average, they are performing better on academic and non-academic metrics.

What are we telling Asian students about equality when they’re told they need to perform above and beyond other racial groups just to get the same level of consideration on their application?

Diversity At All Costs

In Harvard’s 2021-22 Common Data Set, racial and ethnic status was considered at the same relative importance as GPA, application essay and extracurricular activities. Proponents of affirmative action argue that the use of such racial preferences is a necessity to create diversity and that there is no other way to account for systemic inequalities that Latino and Black applicants face leading up to college. First, discriminating against a specific race (as evidenced above) to combat inequality or reach diversity is a hypocritical solution. Second, it is incorrect to believe that diversity can be traded off for academic quality in order to combat racial disparities.

To preface, yes, diversity does benefit education. When facing sociological and philosophical questions, different perspectives enhance classroom discussion. However, this only goes so far. College is about hearing diverse opinions, but most importantly the success of students. Diversity does not improve any student’s performance in classes such as statistics, chemistry, finance, etc. Scoring higher on the SAT or your GPA does however serve as an accurate gauge for success in not just these studies, but all. Race and academic performance should not be given the same level of importance when diversity comprises only a small part of what college work involves.

In a 2012 study, Duke University economist Peter Arcidiacono found that Black and Latino students, specifically whose academics wouldn’t normally gain them admission, were the most likely to drop out of STEM fields and economics. Furthermore, out of students who dropped out of those majors, the same Black and Latino students were the most likely to have done so due to “lack of pre-college academic preparation” or “academic difficulty in the major course requirements.”

As evidenced, minority students who gain admission because of racial preference do not do better once accepted. Giving racial preferences in admissions only creates an optical view of equality. When you set different standards of merit for different population groups, you will get a disparity in performance at the college level. Attempting to institutionalize racial preferences only concedes the disparity and leaves its underlying causes to be ignored. Sacrificing academic quality in the name of diversity doesn’t help anyone.

Without addressing the systemic challenges that occur well before college, which include unequal access to testing and proper schooling, minority students who gain admission determinant on their race will enter college unprepared for the academic arena that awaits them. The focus should be on how to bring Black and Latino applicants up to the standards rather than changing the standards for them — this would have to occur outside of colleges and in primary/secondary schooling along with other social systems.

The issues that proponents of affirmative action work for are very real. Inequality is a major issue in our country, but there are better ways to solve this than by discriminating against a specific race and creating a false sense of equality.

Better Alternatives

Proponents of affirmative action argue that without considering race, the proportion of underrepresented minorities in colleges would immediately decrease. Working to build up the performance capacities of minorities so that they’re on equal footing is a long process. Therefore, I offer three alternatives to the admissions process which have been advocated for by SFFA and would keep diversity while remaining race-neutral.

The first change that should be made, regardless of the decision on affirmative action, is to remove admissions based on parental status as alumni, donors and faculty. Preferences to these applicants often bias rich white students who would otherwise not gain an acceptance. SFFA cited a simulation in which they removed admits that were children of alumni, donors, and Harvard faculty. Doing so increased all minorities’ admission proportions.

The second change should be through the consideration of socioeconomic status at the same importance as race is now. This change would help increase the admit rate of Black and Latino students who are, on average, less wealthy, and it would tackle the root of systemic inequalities better. It would not hold an effect on rich Black and Latino students who don’t face the challenges said to be in testing and schooling inequality. It would however, benefit applicants, minorities or not, who had to overcome lack of opportunity.

The third change is through automatic admissions based on class rank or other academic standings. In Fisher v University of Texas (2016), the University of Texas confirmed that the race-neutral alternative of automatically admitting students who fell in the top 10% of their class “effectively compensated for the loss of affirmative action”. The 2004 entering class at the University of Texas at Austin had a higher proportion of African-American, Asian-American, and Hispanic students than it did in 1996, the last year that the University system used race-conscious admissions.

While the focus should be on getting all disadvantaged minorities the support to reach merit standards (in the 18 years prior to college), there are clear short-term alternatives to affirmative action that will lead to immediate greater diversity on campuses, without discriminating against a specific race.

In opening arguments, Harvard’s attorney Seth Waxman acknowledged the district court’s finding that “race is determinative for 45 percent of Blacks and Hispanics who get into Harvard.” If we want to tell the next generation that they shouldn’t worry about their skin color, then we should stop making it matter so much.

Being a Latino, I want to know that my college admission was determined by my merit, not by the color of my skin.