Trinity forward, Justin Davis, blows by the defender and throws down a vicious dunk. The crowd erupts and coaches call plays as the Saints hustle back to defend, but he barely hears it.

Davis, a captain for the Varsity basketball team, is deaf and has been since birth, but he refuses to let his condition get in the way of his love for basketball.

In order to compensate for his hearing impairment, Davis reads lips and occasionally uses sign language, which allows him to understand what people are saying in normal conversation, a trait that many take for granted.

“Reading lips helps for everything, so most of the time I read lips, but if I was across a loud gym, I would sign to my parents,” Davis said.

When reading lips, Davis has to be looking at the person that is communicating with him at all times. This became an issue when he moved up to the varsity team as a junior because Davis couldn’t afford to take his eyes off the game in order to get the play call from a coach or teammate. Trinity varsity basketball head coach, Anthony DiGiovanni, solved this problem by creating a play calling system in which he and point guard, Javon Bennett, use hand signals to call the plays. This system allows Davis to quickly glance over at the bench to receive the play calls without getting significantly distracted from the game.

“Coach DiGiovanni is really good at calling the plays on his fingers, and I have really good chemistry with Javon,” Davis said. “I feel like I can play really well with just about anybody without needing to talk to them.”

While the system is very effective, it doesn’t solve every problem. Davis occasionally continues playing after the referee has blown his whistle to stop play.

“Sometimes I just don’t hear the ref’s whistle, and I keep playing,” Davis said. “It can be embarrassing at times.”

By rule, playing through the ref’s whistle is a technical foul, however, DiGiovanni would inform the referee of Davis’ condition before the game in order to avoid a foul call for Davis’ unintentional actions.

Throughout his varsity career, Davis has been a key part to the Saints’ success. Standing at 6’6”, Davis’ athleticism, basketball knowledge and work ethic make him a tough matchup for opposing players.

After coaching Davis for two years, DiGiovanni applauds his mentality.

“With his hearing disability, it would be really easy for him to come up with excuses, but when someone wants something bad enough, they can go out and get it as long as they are willing to put in the time and work,” DiGiovanni said. “That’s exactly what he’s done. He’s a gym rat, and he just loves to play. If there’s a game on or a gym open then he’s out there playing.”

With his competitive spirit and positive outlook on life, Davis views his condition as motivation to succeed, rather than a disability.

“I’m often asked whether being deaf is a gift or a curse, and despite the obvious drawbacks, I don’t believe I’d be as successful as I am with normal hearing,” Davis said.

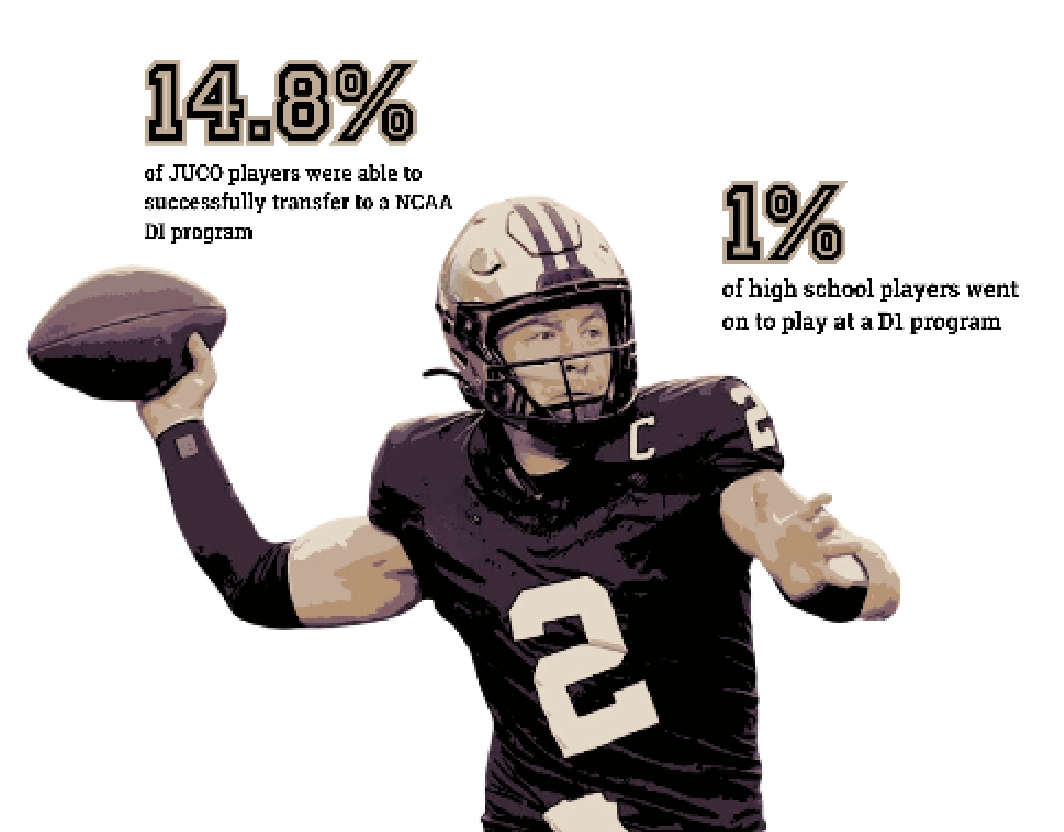

Davis connects this idea to his recruitment, which consists of many schools, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology, California Institute of Technology and Babson College, just to name a few. Overall, he believes that his disability has given him a leg up on other recruits.

“I think that my hearing disability has actually set me apart because it’s special,” Davis said. “They’ll remember me because I’m deaf.”