For decades, college athletes have been significant contributors to a $15 billion industry, benefiting college athletic programs, broadcasting networks and the NCAA. Until recently, college athletes were prohibited from profiting from any athletic endeavors despite generating revenue for others.

On July 1, 2021, following years of controversy surrounding athletic compensation, the NCAA altered its regulations, enabling student-athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness (NIL).

One year after this change, athletes have received an estimated $917 million through NIL deals, and the NIL market is now valued at over $1 billion annually.

“I think when name, image and likeness first came around it completely opened a door for athletes and it was a great opportunity,” Athletic Director Collin Sullivan said.

To attract NIL deals, college athletes often partner with local businesses, restaurants or donor-driven organizations called collectives. Collectives use donor funds to create opportunities for athletes to make money. Despite only being a part of about 20 percent of NIL activities, collectives account for nearly 80 percent of athletes’ compensation.

According to Opendorse, the leading athletic marketplace for NIL, the average NIL deal for Division I athletes is worth $1,300 while the median compensation is only $65. The majority of athletes, especially those at non-power five schools, receive less than the average compensation of an NIL deal, so there is great inequity between higher-profile athletes and lesser-known ones.

Trinity alum and current USF offensive lineman Cole Best has received five NIL deals from local businesses and collectives. Over his career, Best has profited more than $10,000 from deals with businesses including Hooters, Portillo’s, and the Fowler Ave Collective. Best has played against some of the top-ranked schools in the nation and recognizes that high-performing athletes deserve higher compensation because of their appeal to both businesses and fans.

“I think everyone should have an opportunity to make something but better performance is going to pay more because it’s a performance-based industry,” Best said.

While performance is directly correlated to NIL earnings, social media plays a role as well. Livvy Dunne, the highest-paid female college athlete in the nation, earns almost $3.5 million annually. Although Dunne is an excellent gymnast at one of the top programs in the nation, her fame and popularity is mostly attributed to her social media presence. In a similar sense, Bronny James utilizes the James family name to strengthen his presence on social media. Despite barely cracking the top 20 players in his class, James earns $6.2 million annually, making him the highest-paid college athlete in the nation.

Over the past two years, trouble regulating collectives’ power and extensive deals have caused doubts about the future of NILs in collegiate sports. Despite profiting from NIL, Best thinks that new guidelines are necessary to limit its effect on sports.

“It’s getting a little out of hand,” Best said. “I think there needs to be statutes and limitations to it.”

The main critique of the current system argues that wealthy donors have a significant impact on college athletics by offering substantial benefits and perks to athletes, attracting high-level recruits to schools they wouldn’t otherwise choose. For The Win 360, a collective partnered with the University of Utah, recently leased 85 Ram trucks to all scholarship athletes on the Utes’ football team. Donors in charge of the collective agreed to cover the trucks’ leases as long as athletes remain on scholarship and are eligible to play. Junior baseball player and University of Virginia commit Aiden Stillman witnessed the effect of NIL deals while being recruited and doesn’t agree with certain methods used to attract players.

“I think [NIL] can be really beneficial for some players who aren’t given enough scholarship money,” Stillman said. “On the other hand, I think it can be used in a really negative way when schools and collectives bribe players to go to certain schools.”

Like Stillman, Sullivan worries about some of the unintended consequences of the new NIL culture. Specifically, he’s concerned with how NIL deals can affect team chemistry for athletes who feel they are deserving of greater compensation than their teammates.

Team chemistry has not only been harmed by NIL but also by new transfer portal rules implemented in 2021. These rules allow a one-time transfer without requiring the athlete to sit out for one year, which used to be the case. With the addition of NIL, the transfer portal has become more active as well-performing athletes are choosing to transfer to schools where they can make more money without a transfer penalty. Sullivan recognizes that both the trading portal and recruiting athletes through NIL have made it so that it is more difficult for coaches to develop a team over multiple years.

“It used to be if you were really a high-quality coach, you were going to build a program where you recruit younger kids to develop them,” Sullivan said. “Now [coaches] have to build a team in one year, and are going to essentially reload every year with transfers.”

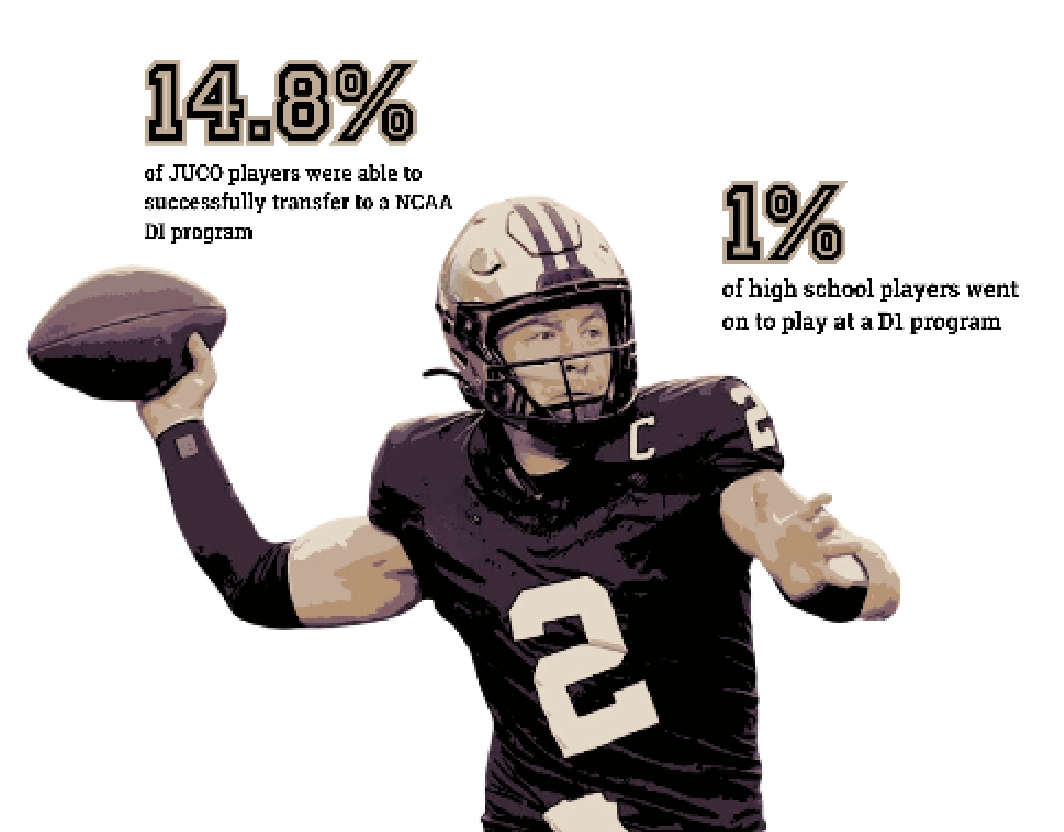

Mid-major schools, which participate at the Division I level but aren’t part of the power-five, have also faced consequences since the addition of NIL and new transfer portal regulations. Less popular programs often lack the financial support from boosters and collectives to compete with high-end athletic schools like the University of Alabama, which attract both recruits and transfers. Sullivan mentioned that teams reloading every year with transfers commonly take players who performed well at these less successful programs, making it very difficult for mid-majors to find success.

“As players perform well at the mid-major level, often they’re going to have the opportunity to transfer to a high-level school where there could be more NIL money that isn’t available at the mid-major level,” Sullivan said. “There’s limited resources with respect to collectives and outside funding at the mid-majors, and most of their resources are going to program development as opposed to in the pocket of players.”

With the recent rule changes affecting the culture of college sports, many fans are worried about the heavy impact financial incentives will have on college athletes. Best said that he has been a lifelong football fan and prefers college athletics over professional sports, which he believes are too centered around politics and money.

“I like [NIL] but only to an extent,” Best said. “It’s really affected recruiting. I live and breathe football and I love the culture so I just hate to see money come in the way of that.”