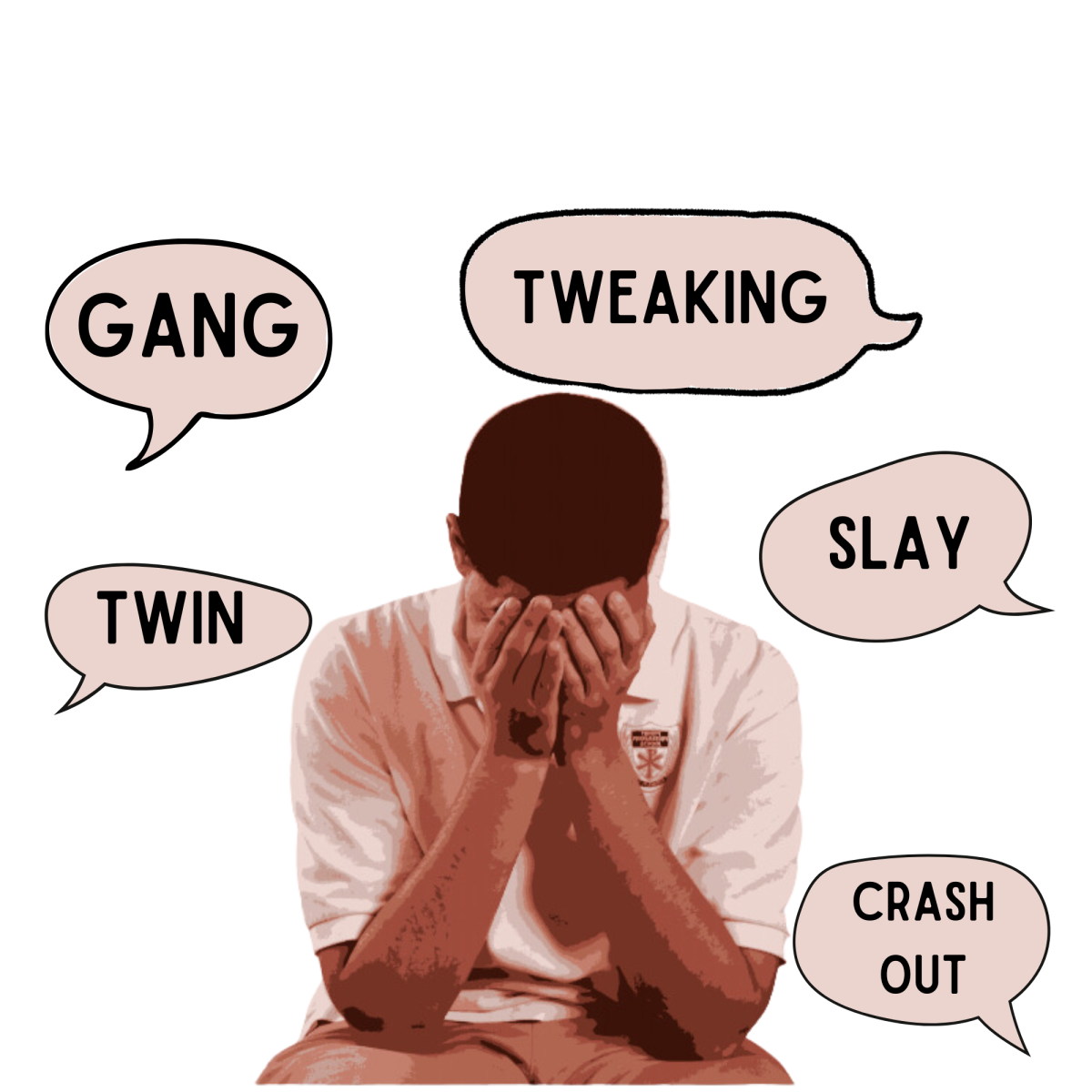

“Gang”

“Twin”

“Slay”

“Tweaking”

“Crash Out”

You may have used phrases like these on campus or online, maybe to be funny or to fit in. However, what many are not aware of is the impact such words have. These phrases all have roots in African-American English (AAE).

Usage of AAE becomes an issue once a simple fact is acknowledged: Black people can’t speak that way without judgment from greater society.

A 2021 study by Baylor University found that 24.9% of the adjectives used to describe individuals who “sounded Black” were associated with being “uneducated,” while 19.5% of responses included the word “poor” for Black people. What these statistics show is that AAE is ultimately viewed as uneducated despite the intricacies and nuances of the language.

“African-American ways of languaging are as complex as any other language [and] have unique evolutionary histories which do not differ from those of Korean or French,” Assistant Professor of Language Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Kelly Wright said.

AAE began as a means to communicate with other enslaved persons, preserve legacy and document lives. During the Great Migration, AAE flourished as Black Americans settled into their communities and individual dialects began to form. Phrases like “slay” were born in LGBTQIA+ Black spaces and used by members of the community as well as women.

Despite their history and significance to the Black community, dictionaries continue to treat AAE as “informal” or “slang.” Merriam-Webster defines slay as “to be exceptionally impressive,” which for all intents and purposes is correct. The issue arises when a word that has served as a cultural touchstone for decades is reduced to the label “informal.”

Instead, the very existence of AAE should serve as a reminder of the history of disenfranchisement within the Black community. Black people have been excluded by a non-Black society so much that an entirely new language was formed.

However, it also serves as a testament to Black people’s determination, community and solidarity.

“Black language use, and all African-American languages, are built on resistance to social, and often physical, domination,” Wright said. “Black people in the Americas have had no choice but to build and sustain a unique culture with … new words, phrases, sounds and signs [that] are continuously generated.”

As Black voices continue to rise in music and media, exposure to AAE has re-entered the stage. Voices like Drake, Beyonce and Travis Scott ring out among a non-Black audience, bringing AAE to new ears.

This is not the first time that this has happened either. In the ’90s when artists such as Lauryn Hill, Tupac and Biggie exploded onto the scene, Black culture did too.

“It’s encouraging to see how influential our culture can be, but it can also be upsetting for some people who don’t share hardships of the people that speak [AAE],” sophomore Miles Johnson said.

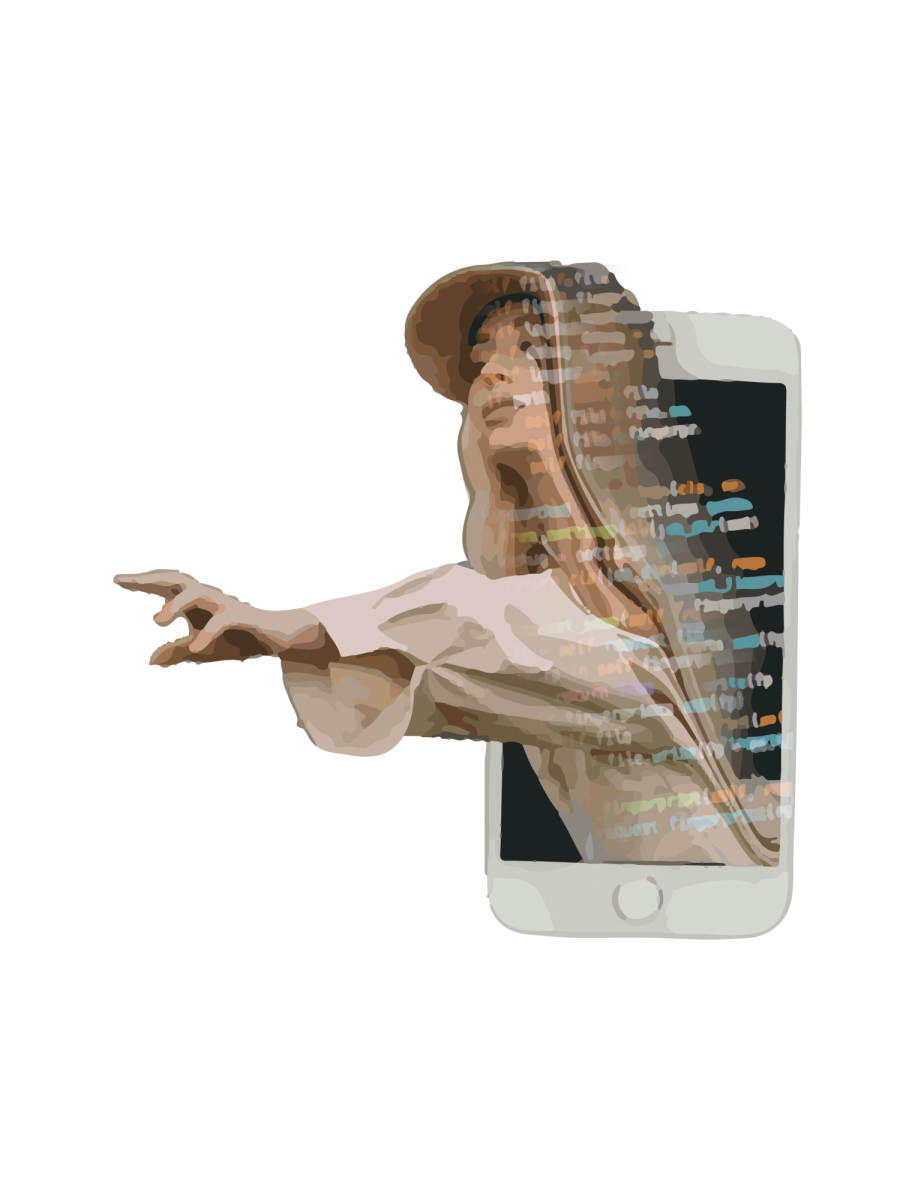

Today, AAE has also begun to soar on social media, a phenomenon Professor of English and African-American Studies Lauren Jackson at Northwestern has acknowledged as “digital Blackface.”

As songs by Black artists have gone viral, non-Black voices have entered social media mimicking what they just heard in a song. Given that it no longer comes from a genuine place of appreciation, it becomes appropriation, but that is what sells.

“[AAE is] humorous to [non-Black people in] that it’s another form of a white minstrel show,” former ethics teacher and PhD candidate in rhetoric Benjamin Gaddis said. “Look at us dressing up our voices like someone else’s.”

Minstrel shows were a common form of entertainment for white people in the early 19th to the early 20th centuries. They featured white people painting their faces black and acting out a caricature of Black people.

Similarly, non-Black users online appropriate AAE to express their ideas in a more dramatized or “comedic” way. Seeing the response, non-Black celebrities continue their mockery, reaching a greater audience, and the cycle continues.

The reason AAE is seen as humorous stems from our standards. What we use as standard English is ultimately an exclusionary form of language. Enslaved people were never given access to the “proper” education, so when the standard form of a language is unattainable for a minority, it can become a tool of oppression as well. In an effort to avoid such oppression, many Blacks actively turn away from AAE.

“I would like it if more people knew that many Black people learn to speak standard English out of fear,” Wright said.

I was taught to speak standard English because my parents did not want me to be profiled. Seeing the media’s portrayal of AAE made my parents scared of me speaking the same way. Thoughts of all of their sacrifices going to waste because people never gave me a chance, entirely because of how I spoke, prompted them to have me conform. However, non-Black people use AAE without the same societal costs Black people experience.

“Appropriation becomes a thing when this natural process of contact or borrowing is amplified by our social hierarchies,” Wright said. “And we see it when a (typically) white person uses the language of a minoritized group without experiencing the social costs minoritized people experience when producing that language naturally.”

Treating AAE as a fad and neglecting its importance while continuing to use it for one’s personal gain is cultural appropriation. Understanding where the line is forces one to think about their actions, not just in a vacuum or as a “joke,” but from a genuine place of deliberation. It is also important to take into consideration the culture one comes from. If you grew up in an environment where AAE was commonplace, then that is just the way in which you speak.

“So, I think that when employing [AAE] rather than using strict boundaries it’s good to extrapolate the meaning of it and where it came from,” Johnson said.

The appropriation of AAE also serves to diminish Black culture. AAE is unique to Black people and their lives. When non-Black people use the same language, it undermines the reason people speak the language. It allows the speaker to bypass the lived experiences of being Black, but reap the benefits of the culture.

It would be a disservice to only focus on the negative though. There are ways to actively cultivate a community surrounding the appreciation of different languages and dialects. Approaching conversations with the intention to learn and grow is the best thing any person can do.

“Black individuality is a luxury, an heirloom to be protected and cherished,” Wright said. “I would like it if more people knew this when they chuckle along with their non-Black friends and colleagues and then in turn look down on Black people using the same language.”