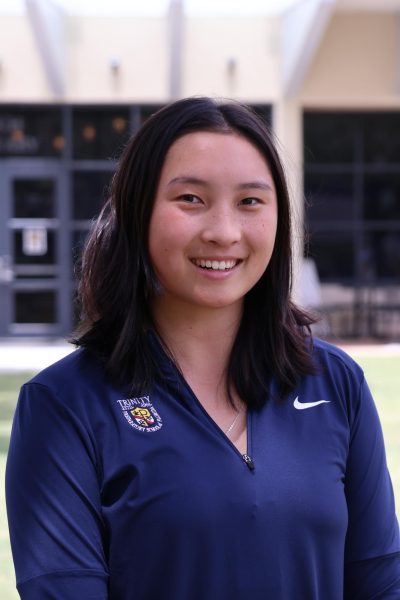

Kristin Durfee comes home at night after a long day at work, sits down at her desk — an organized chaos of handwritten notes — and opens her laptop. She is quickly immersed in a world of mystery, surrounded by the shadowy alleys of New York City, where bodies lay hidden along the streets.

Durfee’s latest book, “Shots,” unfolds in 1930 New York City. The story follows Johanna Kelly, a determined detective racing to solve a high-profile homicide before her department discovers her pregnancy and dismisses her. Balancing the fight for justice with the struggle to maintain her position as a female detective in a male-dominated field, Kelly’s battle is as personal as it is professional.

Durfee, a yearly participant in Trinity’s Author Fest, is no stranger to crafting compelling stories. However, her latest book “Shots” holds special significance — it is the first time she merged two defining aspects of her life: her expertise as a firearms forensics analyst and her lifelong love of writing.

“I had so much fun getting to write in that time period,” Durfee said. “Through my training as a firearms examiner, I knew that was a really pivotal time in the history of firearms identification … it was cool being able to interject a little bit of my day job into a story.”

Durfee has been fascinated by forensics ever since she was 12 years old watching Morgan Freeman play a forensic psychologist in “Kiss the Girls.” However, it was in college where Durfee decided on the specific direction.

“Originally I thought I wanted to get more into pathology,” Durfee said. “[But] I had seen an autopsy and they touched the people’s eyeballs. I was like ‘Nope, I’m out.’ I was fine with everything else, but eyeballs were the line of my squeamishness.”

After choosing firearms forensics as her specialty, Durfee trained under Susan Komar, the first female firearms examiner. Under Komar’s guidance, she mastered techniques like analyzing microscopic markings on cartridge cases ejected during the firing of a weapon — key evidence used to connect firearms to crimes.

“They can say, ‘Yes, this is the gun that fired the cartridge cases from the scene. This is the gun that fired the bullet from the victim’s body,’” Durfee said. “We can place everything together and then hopefully tie it to an individual.”

Drawing on her forensic expertise and a real-life 1894 murder case of Catherin M. Ging, Durfee wrote “Shots” in 2018. The story follows Detective Kelly as she uncovers each murder and finds suspicion in a wealthy man who manipulates an innocent woman (Ruth) into naming him as the beneficiary of her life insurance.

Set in the 1930s, the novel highlights the comparison microscope, a revolutionary forensic tool used to analyze bullets and cartridge cases. Blending historical context with fiction, Durfee features Calvin Goddard, the microscope’s pioneer, as Detective Kelly’s collaborator, using the techniques still employed today to connect the murders.

Originally, the protagonist was Joseph Kelly, a conventional Sherlock Holmes archetype. But after feedback, Durfee reimagined Joseph as Johanna, allowing her to explore the challenges women faced in the 1930s and drawing parallels between Ruth and Johanna, completely different in life but connected in their shared struggles as women.

“[Johanna] just works so much more naturally,” Durfee said. “I think as a woman you access these things [such as] getting to see the sexism within her department … [Both are] in similar positions of being women who are trying to work and make it in the world, just on opposite ends of that coin.”

In sharing their perspectives, Durfee hopes to shed light on women’s experiences with sexism in the past as well as modern times. Her portrayal of sexism in the 1930s resonates with her own experiences in the modern workplace, where people interrupted her presentation to speak over her or to lawyers undermining her abilities because she was a woman.

“I had attorneys be very aggressive to me,” Durfee said. “‘Oh, you’re just a woman. How could you know anything about firearms?’ It’s just knowledge. It’s not inherently feminine or masculine to know how something works.”

The audience sees the injustice in Kelly’s perspective with people constantly questioning her abilities as well as her fear of failing before the repercussions of her hidden pregnancy catch up to her. While Kelly manages to debunk social norms, others like Ruth, who were just as capable, lose their rationality and confidence as they fall under societal pressures.

“I wanted to give a level of empathy to a reader of how a woman could be the victim of her circumstances,” Durfee said. “I want you to walk away and have a little bit more sympathy for historical female figures that we may brush off as being silly or whatever.”

Empathy is not exclusive to women. Durfee emphasizes the importance of humanizing all perspectives. Often, people only consume impersonal headlines of tragedy circulating in the news without taking a moment to realize that they are real people. Because Durfee receives the vessels that deliver these headlines everyday, she hopes to inspire readers to develop greater compassion not only for the victims portrayed in stories but also for real-life victims of crime.

“Especially with true crime, because it is so fascinating, people do just love the whole peering through the window part of it,” Durfee said. “But sometimes that removes us in such a way that we forget that there’s still people and that this was their entire life. They still had a whole family. They still had hopes and dreams. They’re more than the headline of what happened to them.”

Durfee’s ultimate goal in “Shots” is to create a new perspective for her readers — whether that is understanding the struggles of historical figures, appreciating the intricacies of forensic science or simply feeling the thrill of a gripping mystery.

“As humans you are drawn to stories that either make you feel something you haven’t felt before whether it’s love, tension, adventure or adrenaline,” Durfee said. “[Books make] you think of something in a way that you haven’t thought before like when you read a line and go, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve seen 100 sunsets but I’ve never seen them written in just that way where it makes you feel something.’”