After each school shooting, the media looks to find rationale behind such a crisis. While made with good intentions, it is vital we examine how each hypothesis positively and negatively affects society.

Tragic events such as school shootings spiral our nation into a state of confusion. Assigning reason and explanation to the situation is a common coping mechanism, but when these justifications are harmful and inaccurate, it is crucial we reevaluate the way we grieve.

After Columbine, reporters were quick to paint perpetrators as isolated outcasts bullied by their peers. However, this portrayal of a rejected, lone-wolf boy driven to insanity as a result of his peers’ “unkindness” victimizes the person behind the gun and victim-blames the person behind the gun rather than the one looking down the barrel.

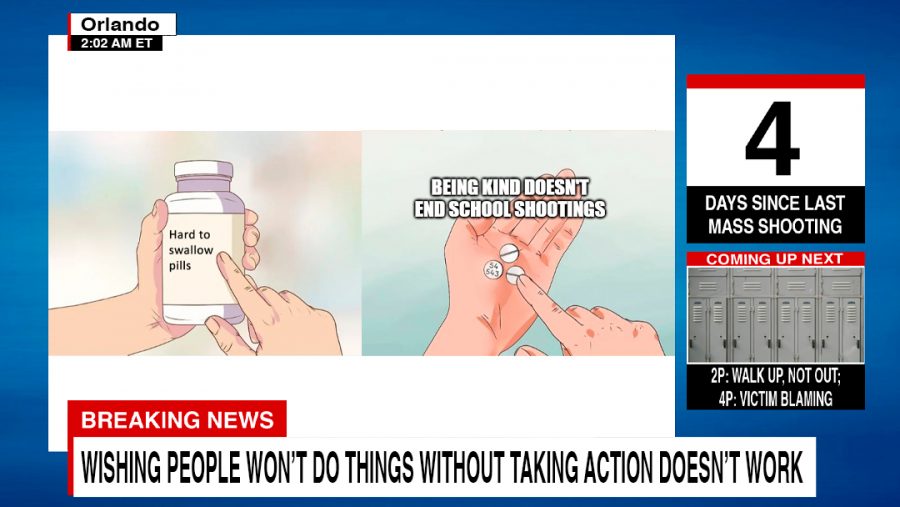

Following the National School Walkout Movement, the counter-movement “Walk-Up, Not Out” was started by parents. The movement was meant to encourage students to spread kindness to more isolated students as an alternative to protesting and calling attention to the recent Parkland school shooting.

While friendship should always be encouraged, claiming it can be used as a sort of currency to prevent a massacre is not only blatantly ignorant but also implies a victim-blaming mentality amongst mostly underaged students.

Teasing, Rejection, and Violence: Case Studies of the School Shootings was a study of 15 cases that found that “acute or chronic rejection—in the form of ostracism, bullying, and/or romantic rejection—was present in all but two of the incidents.”

While romantic and social rejection are common similarities among school shooters, we need to view these as red flags, not logical explanations for illogical actions. News reporters need to clarify that this is a correlation, not a causation.

Whether it be social rejection or romantic rejection, victim blaming only wastes time in finding a solution.

Media coverage on a 2018 Sante Fe school shooting focused mostly on the believed cause of the shooting: 16-year-old Shana Fisher’s “rejection” of the perpetrator. Hundreds of headlines read, “Spurned advances provoked Texas school shooting,” implying that Fisher not wanting to date the future perpetrator was the root reason 10 of her peers died that day.

Stories like these get a lot of coverage. The narrative of a “teen romance gone wrong” is nothing but newsworthy, as media coverage capitalizes on the story-book-like elements instead of focusing on the facts.

Likewise, it is not ethical to blame students for not befriending individuals that make them uncomfortable. What reporters failed to acknowledge when painting the Columbine perpetraters as “social outcasts” and victims of bullying, was that the boys reportedly gave Nazi salutes to others on campus, according to psychologist Rebecca Wald. They made other students feel unsafe.

Although the two boys did make people feel uneasy, AP Psychology teacher Donna Walker says the media’s representation of the boys was far from accurate.

“Dylan and Eric became the poster children for the ‘bullied of America,’ but then after people started really diving in and digging through, it just simply wasn’t true,” Walker said. “Dylan was actually quite popular and likable particularly with the girls. It just wasn’t true.”

While the Columbine perpetrators weren’t the bullied outcasts journalists wanted them to be, students still pick up on social cues. Most can figure out violent red flags. If students steer clear of an individual, there is probably a valid reason for it.

Assuming that isolation is a result of a petty juvenile callousness does not give an accurate representation of the fact that students do not and should not have to be friends with individuals that fit a profile of an emotionally disturbed person.

Students are at school to learn, not to prevent the next school shooting by saying hi to a boy who is known to have violent tendencies. We shouldn’t leave underage students responsible to fight mass murder with “acts of kindness.”

“It’s a weird need humans have to justify things and explain things. To take a chaotic, unexplainable situation and make it explainable,” Walker said.