Disney has been, albeit very gradually, making progress in representing all peoples through their princesses. We did get a fish before an Indigenous princess, or Black princess, or an East Asian princess, but at least most of our generation was able to grow up seeing princesses that look like them. However, the purpose of representation is undermined when it ignores the true history of a group. In the case of Pocahontas, the myth of a kind and generous colonizer became a reality for the millions of children and adults who watched the Disney film. Regardless of intention, poor representation can often worsen the situation for the very groups of people that it is supposed to help.

Representation on and behind the screen matters. The choice to not cast Indigenous actors, hire Indigenous screenwriters or platform Indigenous producers is just that — a choice made by those in power. A USC Annenberg study from 2023 that examined patterns of Indigenous representation in Hollywood reported that after analyzing 16 years and 62,000 speaking roles, only 99 of the roles, or 0.001%, were portrayed by Indigenous actors. Whether intentional or not, the message is clear: The industry does not care to portray Indigenous stories.

These are not just numbers, but a representation of a system that continues to attempt to erase the lives of millions of people in the United States and deny their right to exist in the public conscience.

“That invisibility had a big impact because it’s like if I don’t see myself, then do I really exist?” said Kimberly Guerrero, actress and professor of theatre, film and digital production at the University of California Riverside.

Indigenous people are then put in a position where they have to justify their existence on screen.

“I’ll never forget that … my first time in the room with HBO … out of my 15-minute pitch I had to include at least five minutes of helping them understand why Native stories were important and why there was an audience for them because we got told so many times [that] … people don’t care [about Indigenous people],” Guerrero said.

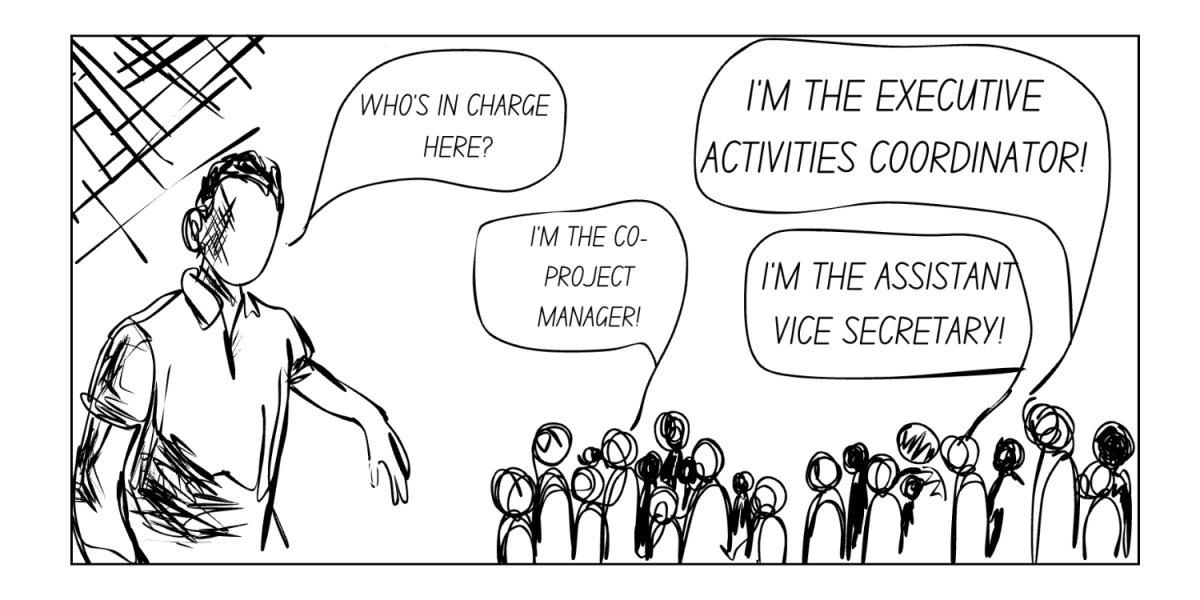

Such conditions create a cycle where Indigenous actors are not hired for major or even minor roles. Their stories never enter the public consciousness, so there is no push to see their lives represented. As a result, Indigenous actors are hired even less, making the likelihood of substantive change even lower.

“A lot of Native scholars and also Native community members talk about the importance of representation and representational sovereignty,” said Dr. Mandy Suhr-Sytsma, professor of Indigenous Studies at Emory University. “The realm of representation being one of many in which native people need and want to assert their sovereignty and to have self-determination over.”

The representation that does exist carries its own issues.

“I feel like it gets really stereotyped, and we see more of old Native American culture like the one that everyone thinks of, big headdresses, stuff like that, and less of just normal people,” junior Chloe Nieves-Ramos said.

The earliest portrayals of Indigenous people in American film came in the form of Buffalo Bill shows. At best, the shows were propaganda, and, more often than not, at worst, they were blatant displays of white supremacy. The shows featured battles between stereotypical Indigenous tribes and the “heroic” cowboys where the cowboys always seemed to win, sometimes even ending in the extermination of herds of buffalo. Those same images were advertised to families as a fun afternoon out.The issues with the Buffalo Bill shows are clear to people now. Romanticizing a culture of murder and brutality to children will only leave them with a skewed perception of reality. So why did people like “Pocahontas” so much?

Disney, out of a desire to push a message that love conquers all, misrepresented the true story of Pocahontas. Amonute, or Matoaka, was 10 years old when John Smith, at 27, originally came to her village. Their interactions never extended past diplomacy between the colonizers and the Powhatan tribe. After a few years of this dynamic, Smith died on a voyage back to England.

In what people viewed as one of the landmark movies for Indigenous representation, real people’s lives fell to the wayside and a myth was immortalized.

“That’s a powerful form of misrepresentation,” Suhr-Sytsma said. “That might seem annoying … but actually [it] has lots of ideology behind it and material consequences attached to it.”

Good representation is simple. When discussing Indigenous representation, Indigenous voices should also be platformed and heard. Non-Indigenous voices should take the backseat and simply listen.

“It’s important to spend … time … on Indigenous created-texts and stories, because I think there’s so much richness there and the work of foregrounding those voices is so important,” Suhr-Sytsma said.

On a larger scale there is obvious room for improvement in the film industry.

“The biggest issue has been they haven’t included us in … above the line positions,” Guerrero said. “That means producers, directors and writers in particular … so you’ll have a situation where they will, at best, bring in a cultural consultant.”

Knowing how to write and accurately portray Indigenous people is just as important as having them play the lead role. Actors should not be the only source of representation in the industry. Likewise, the roles themselves should not be confined to just correcting historically inaccurate portrayals.

“My great grandma was a Cherokee Indian, and she wasn’t like what everyone thinks of when they think of a Native American person,” Nieves-Ramos said. “She was just a normal lady, and I feel like we don’t see as much of that.”

While tackling the issue of a lack of representation on an individual level may seem daunting, it can be as simple as picking up a new TV show. On Hulu, for example, “Reservation Dogs” is the first TV show to be written, directed and produced by a solely Indigenous cast. Supporting shows and movies like that demonstrate that people do want to see actual representation for Indigenous stories.

Outside of supporting the media, people should take the time to do research and understand the history, and more importantly, the current-day standing of Indigenous people. It is important to recognize that the education someone may have received is wrong.

“It happens with every culture where people think they’re being socially aware and politically correct, but actually they’re taking it in a totally different way because everyone’s only seeing it through the lens of what’s been presented to them,” Nieves-Ramos said. “So once again, that’s a big education thing.”

Platforming Indigenous stories and voices outside of media is just as important as within the film space. Fictional stories are not the only stories people have to share with the world. They also have their lives.

“To fight dehumanization with story is paramount because story is medicine,” Guerrero said. “It can be good medicine or … bad.”