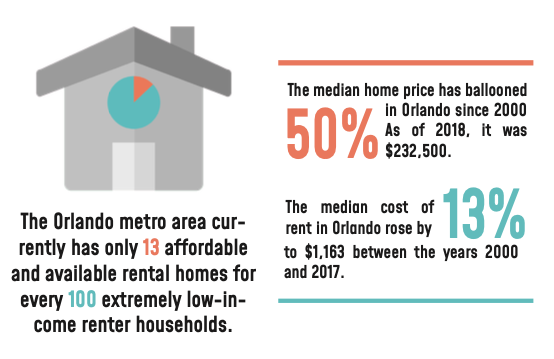

The United States can give out an immeasurable amount of thoughts and prayers. They were in Dallas, where five police officers were gunned down by a vengeful veteran. They were in Orlando, when a self-identified Islamic extremist who pledged allegiance to ISIS walked into an LGBT nightclub and murdered 49 people.

Now, our thoughts and prayers have traveled to Las Vegas, where a sniper, barricaded in a hotel room with dozens of semi-automatic rifles, shot and killed 58 people while causing 489 other casualties. Where will our thoughts and prayers be forced to travel next?

The United States is no stranger to mass shootings. Although our country only contains 5 percent of the world’s population, 31 percent of worldwide public mass shootings occur in the USA, according to the American Sociological Association. Western New Mexico University psychology professor Jennifer Johnston predicts the number of mass shootings to rise in frequency over the next five years if nothing changes, based on the already steady increase over time.

In a paper by Johnston of Western New Mexico University, mass shooters were found to have three main personality traits: depression, social isolation and narcissism. 50 percent of adult mass shooters have a history of psychiatric treatment, and 70 percent of adolescent mass shooters—mostly school shooters—were characterized as “loners” by others around them. Most mass shooters are lonely, disliked by many and feel that they have been “wronged” by their society.

Johnston found that one of the primary defense mechanisms for a narcissistic individual is a desire for fame. In fact, a 2002 study of assassins found that fame is the second most common motive for the shooting they commit, and it is the third most common motive for school shooters. In the twisted minds of mass shooters, infamy is just as valid notoriety as legitimate fame.

With the growth of both news media and social media, mass shooters are given the opportunity for their entire lives to be shared with not only the nation where they reside, but the entire internet-consuming world. In the case of the Las Vegas shooting, the entire life of the shooter was immortalized via online news sources within a week. Readers could learn about his relationship with his doctor, his arsenal of weapons and his gambling abuse. But when it came to coverage of his victims, readers commonly found nothing more than a list of names and photos.

Johnston labels the media’s fascination with mass shooters as the “media contagion” effect. She found that the vast majority of news sources focus their time covering the shooter’s life and methods of crime more than their victims and the impact on the community. A quick Google search of “Las Vegas shooting” days after the event would pull up dozens of results about the shooter but little about the victims.

The public isn’t in the clear on media contagion, either. Johnston’s paper cited a study that analyzed 57 billion tweets, focusing on the word “shooting.” Comparing the frequency of the word with a database of mass shootings, the study found unsettling results. When tweets about certain types of mass shootings went above 10 per million, there was an increase in the possibility of a shooting actually occurring. If the number of tweets about this type of shooting was sustained at 10 per million for at least a month following a recent shooting, the probability of another occurring shortly thereafter was almost 100 percent.

It’s been proven time and time again that both the media and the public are hindering the prevention of further mass shootings. The media, in an effort to gain maximum revenue, plays into the shock factor, posting harrowing photos and videos of the shooting in action, followed by giving detailed accounts of the shooters’ personal life. The public, in stunned fascination, gives the shooter more attention by posting millions of times on social media.

So, what can we do? How do we effectively prevent more mass shootings from occurring?

Johnston’s team found a simple solution—don’t name the shooters. Don’t dish out details of their lives for the public to hysterically consume. Don’t explain how the shooter was able to evade security, purchase 33 guns with no red flags and alter their semi-automatic rifle into a fully automatic killing machine. Johnston predicts that if this “media contagion” is removed following mass shootings, there would be a one-third reduction in such events.

Instead, focus on the victims. Tell the stories of the families ripped apart by senseless violence. Tell of the heroic efforts by ordinary citizens to save the lives of victims. Tell of communities coming together after the violence, like Orlando’s influx of blood donors after the Pulse shooting, and hospital surgeons working 30-hour shifts.

Don’t shock us. Inspire us. And for the victims and all those who were affected, don’t name the shooter.

The lead editorial expresses the opinion of the Trinity Voice editorial staff. Please send comments to [email protected].